The absence of U.N. and O.A.S. condemnations of Washington’s attacks on Venezuela indicates the absolute mafia-type power the U.S. wields in the world.

The United States indicted both Maduro and Flores, who are married, with “narco-terrorism” and related charges and is holding them in New York, where they appeared for the first time in Manhattan federal court on Jan. 5.

Clearly, the United States did not begin its assault on Venezuela on Jan. 3. The hybrid war against Venezuela’s Bolivarian process began in 2001, after the Organic Law of Hydrocarbons was passed as part of a package of 49 laws decreed by former President Hugo Chávez and approved by the National Assembly.

The new Venezuelan law disadvantaged oil conglomerates, most of them from the United States, instead allowing the government to redirect a larger share of oil revenue towards social programmes and long-term national development.

The oil conglomerates, particularly ExxonMobil (Exxon), were furious and have since worked with the U.S. government to try to overthrow not only the government of Venezuela but the entire Bolivarian process.

Hybrid war — through economic, political, informational, and even social means — has been a consistent feature of Venezuelan life for the past quarter century. The illegal attack on Venezuela in 2026 and the kidnapping of its president and first lady are part of this long, continuous war against the working people of this South American country.

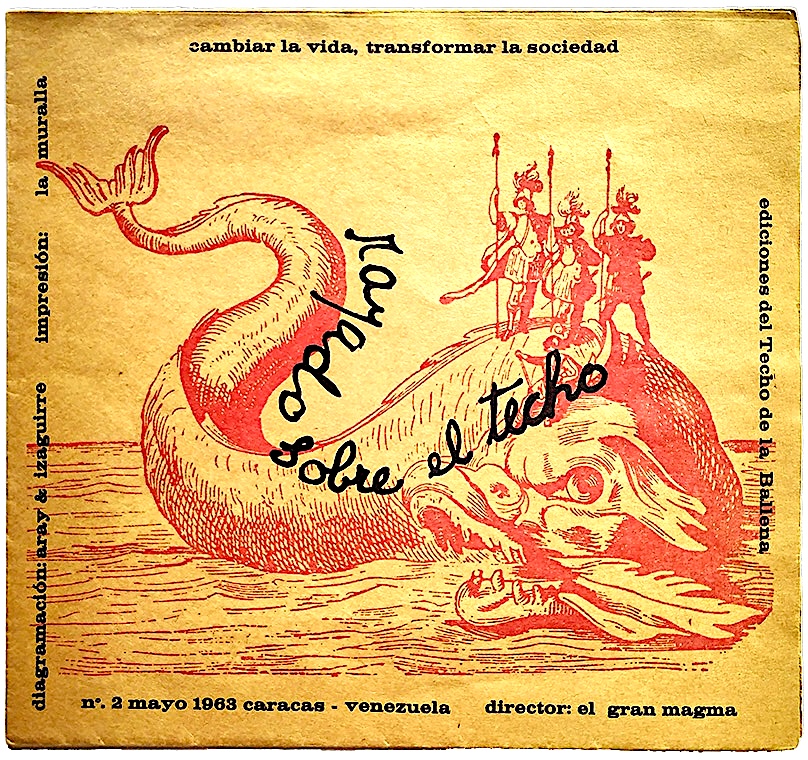

El Techo de la Ballena artists’ collective, Cambiar la vida, transformar la sociedad or Change Life, Transform Society, 1963. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

What makes the attack against Venezuela illegal? Given the way that the United States completely and consistently disregards international law, even as it talks about a “rules-based international order,” it is worthwhile to revisit the basics of international law as well as review the international laws that the country violated with its attack on Venezuela on Jan. 3.

First, when we talk about “international law,” we are referring to legal obligations that states — and, in certain cases, international organisations and individuals — recognise as binding in their relations with one another.

These rules come from two main sources: treaties (written agreements) and customary international law (rules that become binding through consistent state practice and are accepted as law).

A state must consent to be bound by a treaty (which means it should either sign the treaty or accede to it), but it may be bound by customary international law and peremptory norms (jus cogens, or “compelling law,” fundamental rules that bind all states) regardless of whether it has signed any treaty.

For instance, the prohibition against genocide and slavery does not require a state to sign anything, since these prohibitions are recognised as peremptory norms that bind all states as a matter of international law.

Another way of saying this is that some laws are so fundamental that no state can opt out of them. The obligations that I will refer to below come from both sources: treaties (such as the U.N. Charter) and customary international law (including the principle of non-intervention and head-of-state immunity), sometimes interpreted and applied by the International Court of Justice (ICJ, the U.N.’s highest court for disputes between states), whose judgements carry special authority in explaining what international law requires in practice.

- Prohibition of the threat or use of force. There are two key treaties that should restrict the United States’ use of force against other countries:

- The most important is the 1945 Charter of the United Nations, whose Article 2(4) says that all states must refrain from the “threat or use of force” against another state. There are limited exceptions to this, such as if the U.N. Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter (Articles 39–42), determines that there is a “threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression” and then authorises the use of force to “maintain or restore international peace and security,” or if a state is acting in self-defence. Since there is no other exception, the U.S.’ act of aggression against Venezuela is in clear violation of the U.N. Charter, the highest treaty obligation in the interstate system.

- In Latin America, there is also the 1948 Charter of the Organisation of American States (OAS), in which Article 21 says that the “territory of a state is inviolable” and that no “military occupation” or “measures of force” are permitted by one state against another. The OAS Charter follows the U.N. Charter, in which Article 103 makes clear that, where treaty obligations conflict, members’ obligations under the U.N. Charter prevail over those under any other international agreement.

There should already be resolutions at both the U.N. and the OAS to condemn the recent actions of the United States. The absence of such resolutions is a demonstration less of the powerlessness of the interstate system by itself and more of the absolute mafia-type power wielded by the United States in the world.

- Non-intervention in the internal or external affairs of a state. Article 2(7) of the U.N. Charter underscores the centrality of state sovereignty by making it clear that nothing in the Charter authorises the United Nations to intervene in matters “essentially within the domestic jurisdiction” of any state (except through enforcement measures under Chapter VII).

The prohibition of states intervening in one another’s affairs is also set out plainly in Article 19 of the OAS Charter, which says that no state “has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever” in the internal or external affairs of another state, and that includes any “form of interference” — including a military invasion and the seizure of a head of government.

The U.N. Charter and the O.A.S. Charter are treaties, and customary international law reinforces these treaty rules, independently prohibiting intervention.

In the 1986 case Nicaragua vs. United States — brought over Washington’s support for the Contra war and the mining of Nicaragua’s ports — the ICJ affirmed the customary-law principle of non-intervention and applied the rules on the use of force and self-defence (including necessity and proportionality).

Direct attempts by the U.S. to unseat the Venezuelan government, from the attempted coup d’état in 2002 to the kidnapping of President Maduro and Cilia Flores in 2026, are clear violations of these principles, but equally so is the support given by the U.S. to organise armed efforts — such as Operation Gideon (2020), in which the U.S. financed mercenaries to attack the Venezuelan government.

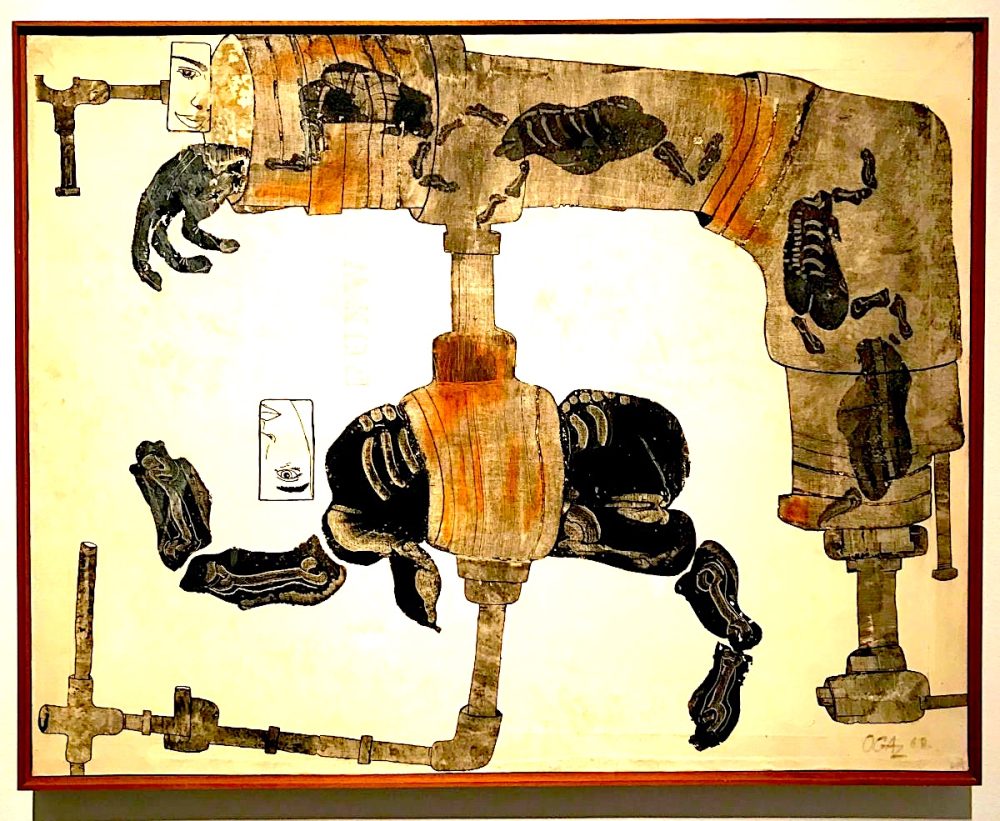

Rolando Peña, El derrame or The Spill, 1997. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

- Violation of head-of-state immunity. When a state asserts criminal, civil, or enforcement jurisdiction over a sitting foreign head of state in contravention of international law — by arresting, prosecuting, detaining or otherwise coercively exercising authority over that person — it violates head-of-state immunity. This is a rule designed to ensure that states can conduct relations without foreign courts seizing one another’s top officials.

Put plainly: as a rule, a foreign domestic court cannot lawfully arrest or try a sitting head of state unless that immunity is waived by that person’s state. There is no stand-alone treaty that codifies this immunity in one place, but it is well established in customary international law and reflected in several instruments and judgements.

The U.N. Convention on Special Missions (1969), for instance, states that a head of state who leads a special mission “shall enjoy … the facilities, privileges and immunities accorded by international law to Heads of State.”

The Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961) separately codifies diplomatic immunity for accredited diplomatic agents, illustrating the broader international-law principle of inviolability for official representatives.

Most importantly, the ICJ, in Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium (2002) — known as the “Arrest Warrant Case,” brought after Belgium issued an international warrant for the DRC’s sitting foreign minister — held that the incumbent foreign minister enjoyed “‘immunity from criminal jurisdiction” and “inviolability” under international law, and that Belgium’s arrest warrant violated those obligations.

There is one major exception in the international system, and it operates within the International Criminal Court (ICC), which prosecutes individuals (not states, as the ICJ does).

Article 27 of the ICC’s Rome Statute provides that official capacity “as a Head of State or Government” does not exempt a person from responsibility under the statute and that immunities “shall not bar the Court from exercising its jurisdiction.”

Under the Rome Statute, the ICC can prosecute individuals for the most serious international crimes — genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression — when national courts are unable or unwilling to act. That is why ICC warrants can be issued even for sitting heads of state or government. This is the legal logic invoked in the ICC’s arrest warrant for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Trump’s brutal attack not only violates international law, but it also raises issues under U.S. law. The 1973 War Powers Resolution requires the U.S. president to consult with Congress “in every possible instance” before introducing U.S. armed forces into hostilities with any state and, if they fail to do so, to report to Congress within 48 hours, with hostilities to end within 60 days absent authorisation. Washington’s contempt for international law is mirrored at home.

At his arraignment on Jan. 5, Maduro said, “I am a prisoner of war.” This is an accurate statement. Maduro and Flores were taken for purely political ends — as part of Washington’s longstanding war against the Global South.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow atChongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and, with Noam Chomsky, The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

No comments:

Post a Comment