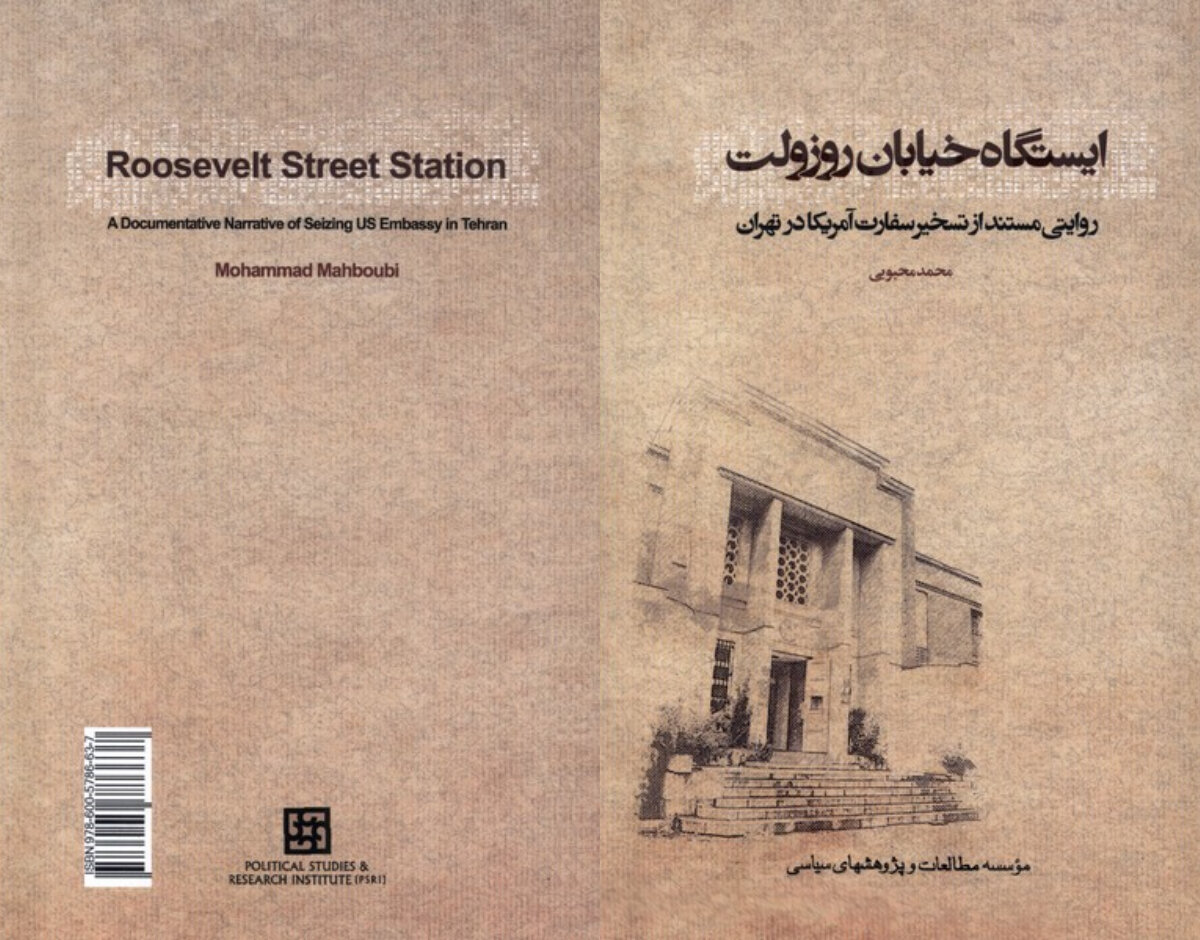

By Mohammad Mahboubi

TEHRAN – One of the most controversial episodes in Iran-U.S. relations is the takeover and detention of American Embassy staff in Tehran in November 1979.

Known in Western discourse as the “Iran Hostage Crisis,” it is commonly referred to in Iran as the “Seizure of the U.S. Espionage Den.” This incident was so polarizing that debate and analysis continue in academic and political circles even today, with some Western international relations experts linking the current state of U.S.-Iran relations directly back to it.

American and European writers have published numerous books and articles on the subject. Some are memoirs by people directly involved, like American officials or detainees, while others are second-hand accounts based on available records and documents.

A common theme across these works is their singular focus on the American perspective, often framing Iranian actions as irrational within an Orientalist view of “Iranian Muslim barbarians.”

In response, “Roosevelt Street Station: A Documentative Narrative of Seizing U.S. Embassy in Tehran” aims to challenge these Western stereotypes. By critiquing such Orientalist analyses, it offers a perspective on the event from an Iranian point of view.

One of the most notable aspects of the book Roosevelt Street Station is its diverse range of sources. Unlike similar works that rely exclusively on American sources—such as government documents and the memoirs of American political figures—this book draws from a wide array of materials.

It examines Iranian organizational records, correspondence between Iranian officials at the time, and even internal documents from the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line –Iranian student group that seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran on November 1979– for the first time, offering a unique perspective on the event and its aftermath. Additionally, interviews with several individuals involved in the incident provide a clearer view of the Iranian standpoint.

Through the study of these Iranian sources, a distinctly different account of the U.S. embassy seizure in Tehran emerges. For example, we see that the beginning of the Iran-U.S. conflict, which persists today, was not the embassy takeover itself. Instead, the November 1979 incident was a response to decades of American involvement in Iran, especially the CIA-led coup against the legitimate government of Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953.

After the Islamic Revolution in February 1979, U.S. embassy activities in Tehran took on a new direction, aimed primarily at opposing—or at least reshaping and undermining—the revolution forces. Iranian society understood this antagonistic stance toward its revolution and feared a repeat of a coup like the one in 1953.

Iranian society’s view of the U.S. embassy’s activities in Tehran was neither a paranoid delusion nor an “Iranian Sèvres syndrome.”

Documents later retrieved from the U.S. embassy and the CIA station in Tehran confirmed this perspective. These CIA documents made it clear that the U.S. embassy was not merely “gathering information as part of its mission”; it frequently conducted “operations within its mission scope.”

Activities included forming political alliances through CIA officers, funding specific political groups, attempting to re-establish electronic surveillance bases known as Tacksman in northeastern Iran, and even organizing military officers for a potential coup—all actions undertaken by the U.S. embassy in Tehran in the months following the Islamic Revolution.

In this light, contrary to the dominant Western narrative that labels the November 1979 event an “illegal attack on the U.S. diplomatic mission in Iran,” Iranians saw it as a “preemptive operation.” The Iranian public, aware that the U.S. embassy was working to counter the Iranian Revolution and potentially repeat the 1953 coup, took preemptive action to protect the survival of their Revolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment