By Mohamad Hammoud

The Fragile Landscape of Post-Assad Syria

The downfall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria was meant to bring stability and hope, but instead, it has unleashed a wave of atrocities against the country’s minorities and ignited fears of a new civil war. Political observers caution that Syria is heading toward a conflict similar to that of Libya, where various factions with differing Islamic ideologies and conflicting agendas vie for power, each backed by diverse regional supporters.

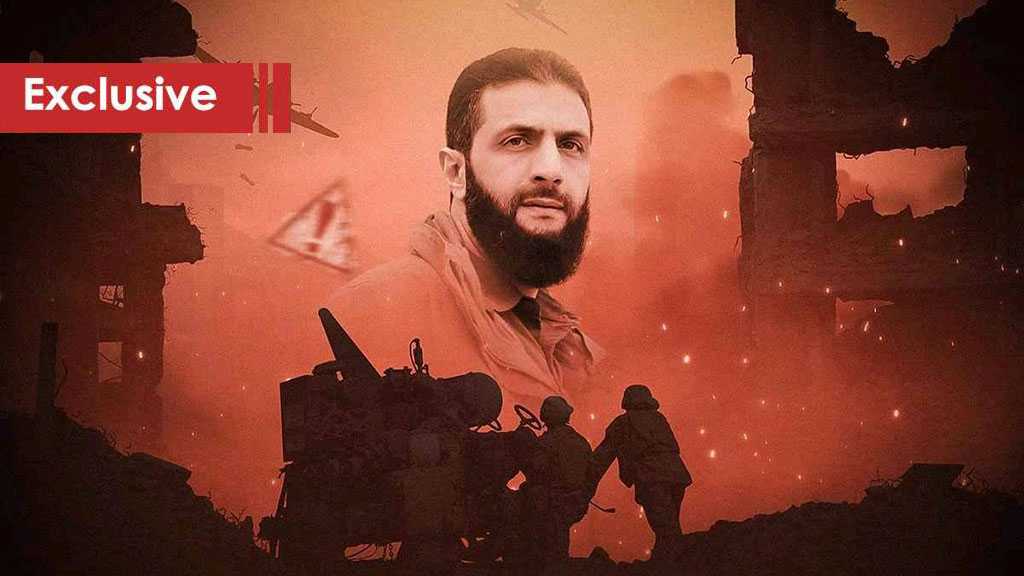

In Syria, these groups have publicly agreed to collaborate under the leadership of Abu Mohammad Al-Jolani, who now claims the title of Syria's president. However, deep-seated tensions and clashing beliefs threaten their fragile unity. As a result, the prospect of a devastating intra-militant "civil" war among factions that once stood together against Assad is increasingly looming.

Jolani’s Evolution and HTS’s Rise

Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, commonly known as Jolani, began his journey within al-Qaeda's Syrian affiliate, Jabhat al-Nusra, where he was instrumental in establishing its presence. As the conflict evolved, he recognized the need for a strategic shift to gain broader legitimacy, leading to the formation of Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham [HTS]. This new entity aimed to distance itself from its extremist roots and present itself as a more “moderate” group, seeking international recognition while solidifying its hold in northwestern Syria. Jolani's shift allowed him to secure crucial support from Turkey, which sought to expand its influence in post-Assad Syria. Consequently, HTS has emerged as a dominant force, controlling significant territories and asserting itself as a key player in the political landscape.

However, Jolani faces the monumental task of reconciling his group’s Islamist agenda with the demands of governance in a diverse society. While he has portrayed himself as a pragmatic leader compared to other jihadist factions, his rule remains tied to radical ideology, creating a volatile environment. Syria’s population includes various sects—Sunni Muslims, Alawites, Kurds and Christians—many of whom may not support Jolani's vision, and some have even fought against each other in the past.

Clashes Among Syrian Factions

HTS's history of conflict with other factions illustrates the deep divisions within Syria's militant movement. The group has engaged in open confrontation with the Syrian National Army [SNA], a Turkish-backed force, over territorial control and ideological differences. Additionally, HTS has clashed with ISIS, which it sees as a rival for influence. Even its parent organization, Al-Qaeda, has found itself at odds with HTS due to divergent strategies and goals. These clashes underscore the challenges of uniting disparate factions with conflicting interests. This phenomenon is not unique to Syria; similar patterns have emerged in Afghanistan, Libya and Iraq, where the collapse of authoritarian regimes led to prolonged civil wars among factions that previously fought together. In each case, ideological differences and competition for resources complicated reconciliation efforts. Syria appears to be following this trajectory, with the potential for civil war growing as it navigates its post-Assad future.

The Ideological Divide

The ideological divide among Syria's factions presents perhaps the greatest obstacle to unity. While groups like HTS, ISIS and Al-Qaeda share a vision of establishing an Islamic state, their interpretations of governance differ significantly. The Muslim Brotherhood [MB], with which HTS has aligned itself, advocates for gradually implementing Sharia law through political engagement rather than armed revolution. In Syria, Turkey has supported MB-aligned factions within the SNA, viewing them as a counterweight to both the Assad regime and more extreme jihadist groups. However, the Brotherhood faces fierce opposition from regional powers like Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt, which perceive it as an existential threat that challenges their authority.

In contrast, al-Qaeda outright rejects democracy, viewing it as a Western-imposed heresy. Instead, it advocates for establishing an Islamic emirate through armed “jihad”. Given this ideological backdrop, HTS has attempted to rebrand itself as a more pragmatic actor; however, its governance in Idlib was deeply authoritarian, enforcing an extreme interpretation of Sharia law and suppressing dissent. This has created tension between its acceptance of Turkish support and its ideological foundations, leading to violent confrontations with SNA factions.

ISIS occupies the most extremist end of the jihadist spectrum. Unlike Al-Qaeda, which sometimes tolerates local alliances, ISIS adheres to a rigid Takfiri ideology that deems all non-adherents—including other Muslims—as apostates deserving death. This absolutism has instigated brutal conflicts with various factions, including HTS and the SNA. Although territorially defeated, ISIS continues to represent a latent threat, poised to exploit any power vacuums that arise.

Regional Patrons and Proxy Conflicts

External powers exacerbate these divides by backing rival factions. Turkey supports HTS and the SNA to counter Kurdish forces and promote Brotherhood governance. However, the clashes between the SNA and HTS over territory and resources reveal Ankara’s struggle to manage its proxies effectively. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the UAE fund Salafi groups opposed to the Brotherhood, perceiving it as a direct threat to their regimes. Their aggressive suppression of Brotherhood-linked movements within their own borders reflects their fear of grassroots mobilization.

The Libyan Parallel

The Syrian conflict bears striking similarities to Libya, where multiple factions backed by different regional powers have fought for control. In Libya, Turkey supported the Tripoli-based government, while Egypt and the UAE backed Khalifa Haftar’s forces, resulting in a prolonged civil war. Although the conflict among factions in Syria has not yet escalated, the country now faces a similar trajectory, with external backers likely to prolong internal rivalries and make stability elusive.

Conclusion

Syria’s militant landscape is a volatile mix of competing ideologies and foreign interests. The divergent visions for the country’s future held by the Muslim Brotherhood, Al-Qaeda-derived factions like HTS, and remnants of ISIS underscore the difficulty of achieving unity. History suggests that these groups are more likely to engage in conflict with one another than to unite. With regional powers exacerbating these divisions, the risk of another civil war among Syria’s militants is alarmingly high.

No comments:

Post a Comment