Not so long ago, in November 2010, I took command of B Troop, 4th Squadron, 4th US Cavalry in a ceremony at Fort Riley, Kansas. It was, for me, a proud day. Army officers are taught to revel in their unit’s history, and the 4th Cavalry Regiment had a long, storied past indeed. On that cool, late fall day, the squadron’s colors – a flag with battle streamers – fluttered. One read: Bud Dajo, Philippine Islands – a reference to one of the regiment’s past battles. The unit crest pictured on the flag and pinned on our uniforms included a volcano and a kris – the traditional wavy-edged sword of the regiment’s Moro opponents in the Philippines – but hardly a trooper in the formation knew a thing about that war, battle, or the 4th Cavalry’s sordid past in the islands.

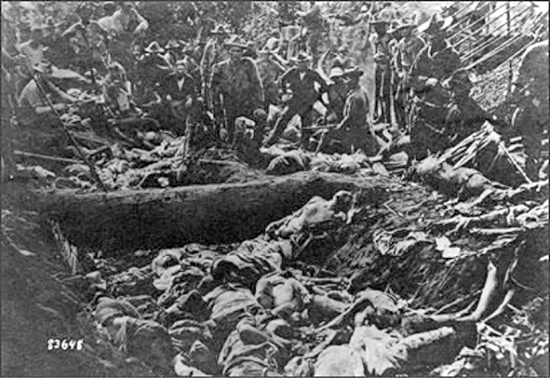

Bud Dajo was hardly a battle at all. It was a massacre. Some 1,000 Moro separatists, including their families, who opposed the US military occupation of Jolo Island, had fled to the crest of a volcano to avoid American conquest and retribution. Then, from 5-8 March 1906, the 4th Cavalry, along with other army formations, bombarded the overmatched Moros – few had firearms at all – then rushed the summit. The Moro men fought desperately and managed to inflict some 20 deaths on the charging American troopers, but they’d never stood a chance. Reaching the volcanic top, the cavalrymen fired down into the crater until all but six defenders and occupants were dead, a 99% casualty rate. The victorious troopers then proudly posed for a photograph, standing above the dead – which included hundreds of women and children – as though they were naught but big game trophies on a safari hunt.

Few Americans remember the US invasion, occupation, and pacification – a neat euphemism, that – of the Philippine Islands, but Filipinos will never forget. Perhaps half a million locals died (one-sixth of the total population) at the hands of superior US military technology, induced disease and starvation. The war also reflected and affected the US Army culture of the day. Most of the generals were veterans of the vicious Indian Wars of extermination in the previous decades. Racially pejorative terms for the Filipinos entered the military vernacular. Some, such as “nigger,” were reappropriated; others, like gugu – thought to be the etymological precursor to the Vietnam-era epithet gook – were new. The war also informed the army’s leadership for many years. The first twelve of the US Army’s chiefs of staff, including General John Pershing of World War I fame, had all served in the Philippines. The legacy was quite long. Even General George Marshall, architect of World War II victory and a future Secretary of State, had served in the islands as a fresh lieutenant.

The war bloodied and frustrated the US Army, too. Some 4,000 soldiers died, many more were wounded, and the conventional conflict and counterinsurgency raged from 1898-1913, making the Philippine War the second longest in American history, after Afghanistan, that is. The war did, in a peculiar moment during the 2016 presidential campaign, briefly earn a shout out from Donald Trump. In order to bolster his own calls for war crimes against terrorists and their families, he told an apocryphal – and debunked – story about how Pershing had once ordered bullets dipped in pig’s blood (considered unclean in Muslim culture), had 49 prisoners executed with them, and then set the one survivor free to inform his comrades of what awaited them should they continue to resist. The result, said Trump, “for 25 years there wasn’t a problem, okay?”

U.S. soldiers pose with Filipino Moro dead after the First Battle of Bud Dajo, March 7, 1906, in Jolo, Philippines.

It made for great rhetoric, but awful history. Not only had the incident never occurred but the war had dragged on for years after even the army’s worst atrocities, including the 1906 Bud Dajo massacre. A cool seven further years, in fact. Besides, Pershing – though himself flawed and later architect of his own volcanic Moro massacre of 200-300 souls in 1913 – had been largely sympathetic to the locals. He learned their language, ate their food, traveled unarmed to meet their leaders, and became the honorary father to a local sultan’s wife. When his superior, General Leonard Wood – who today has a prominent active fort named after him in Missouri – ordered the assault on Bud Dajo, Pershing had surveyed the results and declared “I would not want to have that on my conscience for the fame of Napoleon.”

Back home in the states, many prominent consciences were indeed shocked by the massacre, and, in particular, the trophy photo taken by the victorious troopers. The image flooded the papers, the 1906 version of going viral. At that time, unlike today, there was a substantial (if not majority) anti-imperialist movement brewing. It’s lead literary spokesman, Mark Twain, said of the Bud Dajo “battle,” “We abolished them utterly, leaving not even a baby alive to cry for its dead mother.” These words were hardly trifling, and the rhetoric and activism of anti-imperialists succeeding in getting opposition to empire and the Philippine occupation into the platform of even the highly racist, Jim Crow-era, Democratic Party.

The photograph also galvanized African-American civil rights activists. W.E.B. Du Bois declared the crater image to be “the most illuminating I’ve ever seen,” and considered displaying it on his classroom wall “to impress upon the students what wars and especially wars of conquest really means.”

Nothing even approaching that level of intellectual outrage exists now, as the American Empire spreads its tentacles the world over. Few public intellectuals – to the extent that endangered species even exists these days – even notice the extent of their nation’s ongoing war crimes in the Greater Middle East. Take Afghanistan, for example, the only war longer than the American debacle in the Philippines. After 18 indecisive and bloody years of combat, the US military and its Afghan allies now kill more civilians annually than the vicious Taliban. That ought to be cause for pause, reflection, concern. Only it isn’t, not in Washington, not even in most universities. We’re a long way from Du Bois posting the Bud Dajo picture on his classroom wall.

Men carry the coffin of one of the victims after a drone strike that killed 30 pine nut farmers in Nangarhar province, Afghanistan, on Sept. 19, 2019.

Not that there haven’t been plenty of shocking photos of the civilian victims of US bombing these past weeks. Over the course of just several days in late September, the military (“accidentally,” it claimed) struck two weddings, and a group of thirty innocent pine nut farmers. Total civilian deaths approached 100, with many of the victims (in the weddings) women and children. Their crimes, apparently: gathering while Afghan! That’s right, in militarized Afghanistan, merely forming sizable groups – for ceremonies, funerals, farming – appears, to drone operators and bomber pilots, apparently criminal and threatening.

Far too often, way more routinely than Americans are apt to remember, US aircraft have subsequently slaughtered civilians – thereby bolstering Taliban narratives and recruitment, and sowing distrust of the U.S.-backed Kabul regime. Nevertheless, you’d never know it back here in the safety of the homeland. These war crimes hardly crack mainstream media and the macabre photo evidence barely raises an American eyebrow. That’s apathy manifested as tragedy.

So consider this modest piece of mine, this brief history lesson and connection to contemporary US empire, a plea of sorts to the teachers of America. Want to be a true patriot, a forceful educator, and decent human being? Well, do your students a favor: post the photos of recent US military airstrikes upon civilians in Afghanistan – the war crimes of the 21st century – on your classroom walls. Du Bois, and Twain, would be proud…and that’s hardly bad intellectual company to keep…

Maj. Danny Sjursen

Maj. Danny Sjursen is a retired U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan...

No comments:

Post a Comment