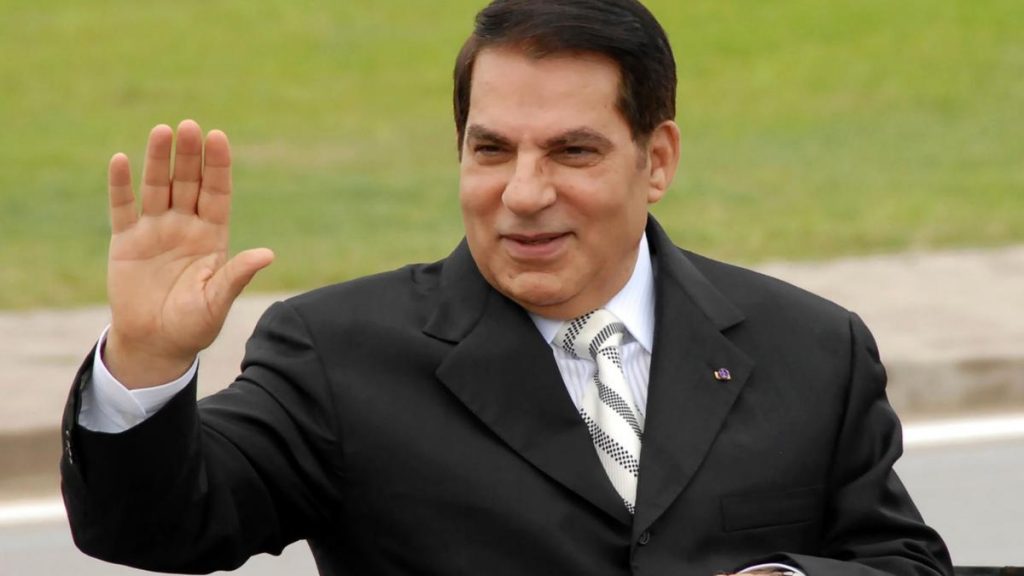

He was the prototypical strong man softened by tactical reforms, blissfully ignorant before the fall, blown off in the violent winds of the Arab Spring. Having come to power in 1987 on the back of a coup against the 84-year-old Habib Bourguiba, whom he accused of senility, Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali was the face of Tunisia till 2011, when he exited his country’s politics in a swift repairing move to Saudi Arabia. Previous whiffs of revolution – for instance, in 2008 in Gafsa – had been contained and quelled by what was a distinct mukharabat-intelligence security state.

Ben Ali had the unwitting humour of generally humourless authoritarian rulers, mirthlessly characterising his reign as one of le changement and “democratic transition”. “I needed to re-establish the rule of law,” he explained to French television after seizing power. “The president was ill, and his inner circle was harmful.”

The military-security apparatus he presided over burgeoned despite his own efforts at reforming social security, education and women’s rights. The Presidential Guard was bloated to some 8,000 members; the National Guard, with its headquarters near Tunis-Carthage International Airport, numbered 20,000. A multiple set of police outfits were also created, including those specifically dealing with universities, tourism and politics.

The sense of non-change marked by extensive surveillance was characterised by indulgent portraits, often enormous, featuring a certain agelessness, a cultish obsession with found on billboard and buildings. Ben Ali could still claim that he was, relative to his despotic peers, more benevolent. Economic stability, in a fashion, was brought for a time, though this had the unfortunate effect of encouraging a needy cronyism. A bigger pie meant greedier hands.

His report card as minister for national security showed that, when needed, he would summon the security forces to do his bidding, crushing the Bread Riots between 1983 and 1984, a protest against the rise in bread prices occasioned by the introduction of an austerity program imposed by the International Monetary Fund.

The sequence of events that saw Ben Ali undone would come to be known as the Jasmine Revolution. There were the spectacular displays of self-inflicted suffering, including the immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, Tunisia’s very own indigenous Jan Palach, who had set himself alight before the tanks of the Warsaw Pact in January 1969. On December 17, 2010, the 26-year-old fruit vendor’s act directed against institutional harassment inflamed protests in Sidi Bouzid.

A country with a national unemployment of 14 percent, numbering as high as 30 percent in the 15 to 24 years age group, was throbbing with revolutionary dissent. Remittances from Tunisians working abroad had fallen; the global financial crisis from 2008 had bitten savagely. Policing, hypersensitive to any Islamist upsurge, had become more aggressive. But looming across the country were the predations of Ben Ali’s kleptomanic family of 140 persons, known colloquially as “The Family”, and a distinctly unholy one at that. Perhaps with a certain tired inevitability, a femme fatale figure was identified: the first lady and Ben Ali’s second wife Leila Trabelsi. The Trabelsi name became shorthand for habitual state corruption.

Something rotten in the state of Tunisia was also discernible to a highly literate populace now able to access diplomatic cables on WikiLeaks, which came to be regarded as something of a golden boy for the revolution. One US government cable from June 23, 2008 stands out: “Whether it’s cash services, land, property, or yes, even your yacht, President Ben Ali’s family is rumoured to covet it and reportedly gets what it wants.” Investment levels had declined; bribery levels had increased.

US ambassador Robert F. Godec also noted the exploits of the First Lady’s brother, Belhassen Trabelsi, whose rapacity included the illegal acquisition of “an airline, several hotels, one of Tunisia’s two private radio stations, car assembly plants, Ford distribution, a real estate development company, and the list goes on.” For all that, he remained merely “one of Leila’s ten known siblings, each with their own children. Among this large extended family, Leila’s brother Moncef and nephew Imed are also particularly important actors.”

The twenty-eight days of protest also saw the extensive, coordinated use of social media, another technological manifestation that continues to terrify states of different ideological shades. In a dry article on the subject – again, another piece that reads oddly given the current rage against social media as a corrupting, conniving incubator of “fake news” – Anita Breuer, Todd Landman and Dorothea Farquhar suggested that, “Social network platforms such as Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook have multiplied the possibilities for retrieval and dissemination of political information and thus afford the Internet user a variety of supplemental and relatively low cost access points to political information and engagement.”

Other factors also came together. For one thing, the Tunisian army and senior officials refused to turn the guns on protesters with quite the same interest as other regimes might have done. What transpired was certainly a set of circumstances more profound in change than other states swept up in Arab spring time. For one, the ruling Rassemblement constitutionnel démocratique (RCD) was given the heave-ho, remarkable for the fact that it had been the party of independence.

As the books, and political system, were being reordered and rescripted, a Tunisian court sentenced Ben Ali and Leila Trabelsi in absentia to 35 years in prison, topped by a $66 million fine for corruption and embezzlement. The highlights of the trial suggest those of a gangster keen on guns, drugs and archaeological treasures.

The Arab Spring seems, to a large extent, a flutter of history and packed with a good deal of wishful thinking; but for a time, it seemed that lasting change might take place, staged as grand theatrical acts of protest against military thuggery. The stable of Egyptian politics was turned out; there were protests across North Africa stretching to Iran. But the strong men returned, and authoritarianism reasserted itself. We bear witness to a flirt of history rather than any lasting consummation of change. Tunisia, however, proved the holdout exception. Ben Ali might well have counted himself unlucky, a victim of posterity’s considerable, mocking condescension.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne.

No comments:

Post a Comment