Ian Wallace

Military aid to Egypt has become an entitlement programme that often facilitates human rights abuses

US President Donald Trump welcomes Egypt's President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi at the White House in Washington (Reuters)

The death of former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi just weeks before the sixth anniversary of the military coup that ousted him from office is a dark - but fitting - symbol of Egypt’s devolution back into autocracy.

But after an unpredictable decade of upheaval, revolution, and counter-revolution one thing has remained constant - the annual flow of billions of dollars in US military aid.

An entitled programme

Successive US administrations have treated military aid to Egypt almost as an entitlement programme. And while previous US administrations have viewed Egypt as vital to maintaining regional stability, the anniversary of the deadly putsch and Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s brutal rule warrant serious reevaluation of this relationship in Washington.

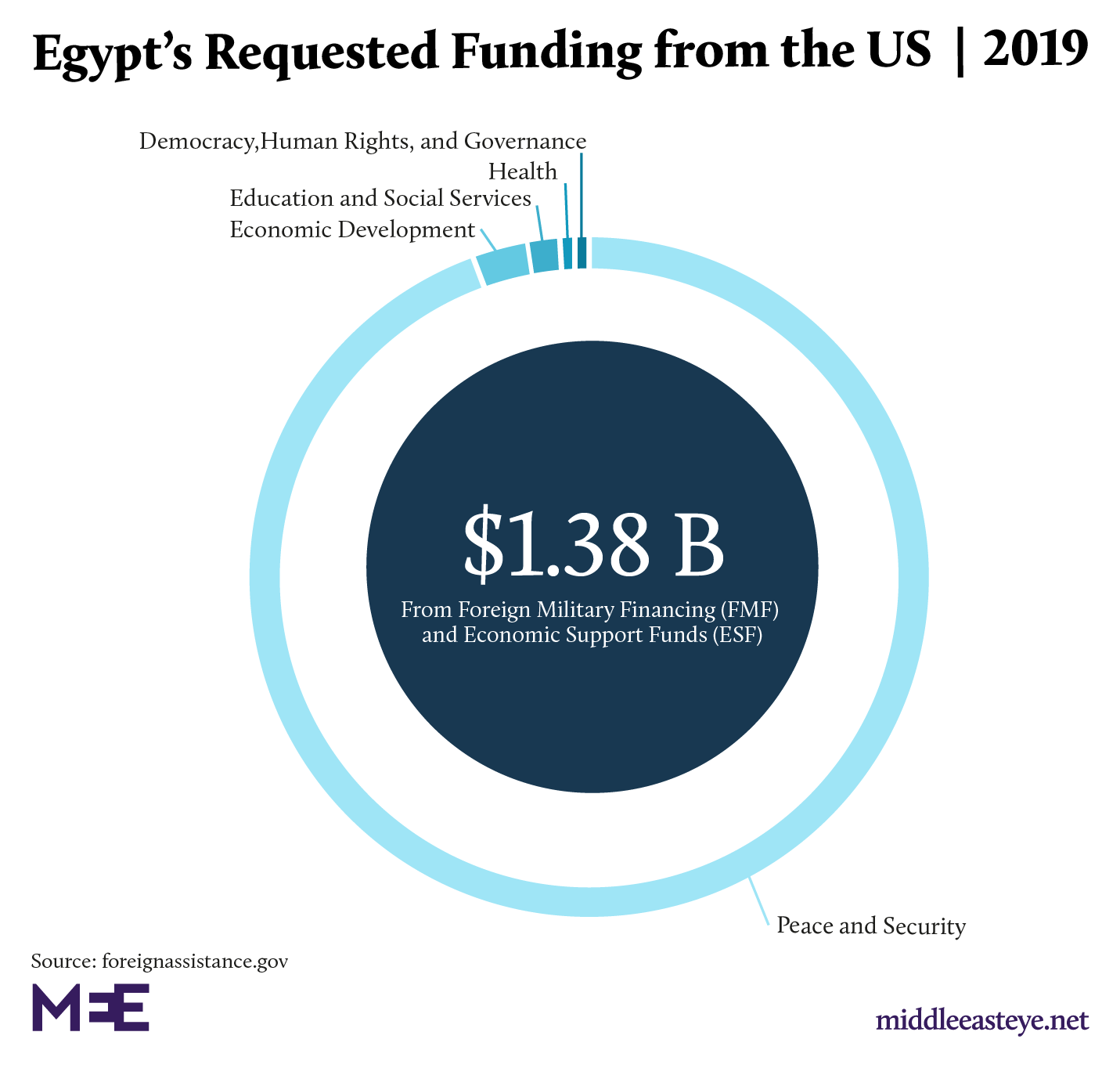

Since the 1970s the US has provided substantial military aid to Egypt as part of the Egypt-Israel peace agreement set at Camp David. Between 1946 and 2019, the United States has provided Egypt with $83bn in bilateral foreign aid, not adjusted for inflation. In 2019 alone, Cairo was allocated $1.307bn in US military assistance.

Despite such a staggering investment, the US found itself unable to challenge the violence of the 2013 coup

Unfortunately, despite such a staggering investment, the United States found itself unable to challenge the violence of the 2013 coup that was largely supported by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Though then secretary of state John Kerry claimed that the events of 2013 were about "restoring democracy", it is difficult to view it as anything other than a military coup against a democratically elected civilian government.

Unprecedented rights violations

As such, the United States was legally obligated to suspend all aid to Egypt under the Foreign Assistance Act. In an impressive display of linguistic gymnastics, former US President Barack Obama never referred to the events of July 3rd, 2013 as a coup, nor did he suspend more than a symbolic amount of assistance.

Meanwhile, the aftermath saw an unprecedented level of human rights violations.

The coup's aftermath saw an unprecedented level of human rights violations

In an attempt to assuage international concerns over Egypt’s coup, Obama failed to take a stand on Cairo’s democracy, saying, “[Morsi’s] government was not inclusive and did not respect the views of all Egyptians." The president had never before articulated this disturbingly inconsistent standard.

Obama’s response to the Rabaa massacre, where over a thousand demonstrators were killed when the military dispersed a sit-in, and other post-coup violence was lacklustre. He did not freeze military assistance until October 2013, nearly two months after the violent crackdown began.

The amount frozen, however, was not all that significant, only a couple hundred million dollars and the suspension of shipments of large weapons systems. Meanwhile, Egypt still received military aid over $1.2bn in 2013 and over $1.3bn in 2014.

Moreover, in a subsequent visit to Egypt, Kerry reassured the Egyptian military of continued cooperation, thereby undermining the freeze’s coercive value.

The freeze was lifted in 2015 despite lack of progress on human rights or democratisation.

Although there was a temporary hold in 2018 from which Secretary of State Mike Pompeo later released all assistance, Egypt still received over $9bn in military assistance between 2013 and 2019. The cycle of withholding assistance to Egypt has essentially become part of a regular pattern.

Public slaps

This pattern indicates that the US is more interested in using temporary holds on symbolic amounts of aid to serve as public slaps on the wrist rather than deliver legitimate rebukes to regime conduct. These “freezes” have not been sufficient in scope or duration to meaningfully impact Egypt’s conduct.

US spends over $1.3bn annually in return for an autocrat masking human rights violations as counter-terrorism measures

In May 2019, Human Rights Watch raised concerns over military assistance perpetuating human rights abuses in Sinai in the name of counter-terrorism. Previously, the Egyptian military had lethally attacked a group of mostly Mexican tourists using US-made Apache helicopters.

Late this June Amnesty reported on a "wave of arbitrary arrests" which targeted several secular activists and a former MP. Yet the current administration shows little sign of changing policy. As such, military aid to Egypt has essentially become an entitlement programme that often facilitates human rights abuses more successfully than American strategic interests.

Mubarak 2.0

Under Sisi’s leadership, the progress achieved following Egypt’s first democratic election has been more than reversed. Between the targeting of Copts, journalists, Islamists and liberals, human rights practices in Egypt have deteriorated rapidly.

Sisi resembles a Mubarak 2.0, but on many accounts he runs a more repressive regime.

The United States fails to use military assistance as a tool to make its partners accountable. A foreign policy informed by human rights and reform must take precedence over cooperation with the Egyptian military.

Military assistance heavily skews towards partners with little interest in long-term governance reforms – and, as Egypt demonstrates, some US partner countries receive the same amount each year regardless of their behaviour.

If we let these concerns dictate policy and don’t cut or condition assistance, the return value on the assistance we provide plummets. Instead, the US consistently fails to leverage aid to modify partner behaviour for the improvement of human rights practices.From this foreign policy weakness, Sisi has learned to manipulate great power politics, increasing weapons imports from France and Russia, thereby reducing the potential impact of US assistance. Many voice concerns that enforcing conditions and cutting US military aid would permanently jeopardise US-Egypt relations, and that Sisi would replace US-made weapons with Russian ones. However, our history of suspending arms shipments to Egypt demonstrates that this may not be the case.

In light of the coup’s sixth anniversary, growing human rights abuses, and President Morsi’s death, members of Congress and foreign policy advisors ought to ask themselves, "Is the violence and repression of Egyptian society worth the supposed gains for international security?"

Presently we spend over $1.3bn annually in return for an autocrat masking human rights violations as counter-terrorism measures.

No comments:

Post a Comment