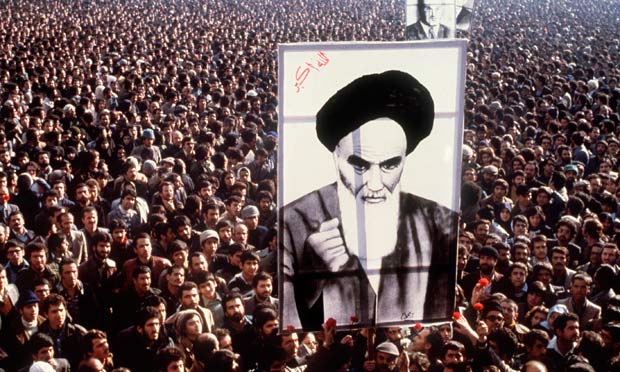

Protesters hold an image of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini during the 1979 Iranian Revolution

by Ghoncheh Tazmini

The Stena Impero, a 30 thousand tonne British-flagged tanker, was seized in the Persian Gulf by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps on July 19. Sailing in the Strait of Hormuz, the world’s key maritime chokepoint, the vessel was impounded by Iranian authorities, who claimed that it was ‘violating international maritime rules’ by causing pollution in the vital waterway. Its 23 crew members are reportedly “safe” in Iranian custody. Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei declared that the seizure was a retaliatory move for Britain’s role in detaining an Iranian tanker, the Grace 1, off Gibraltar earlier in July. The incident has contributed to a simmering standoff between Tehran and Washington—a crisis that is inching perilously close to war.

The Stena Impero seizure can tell us a lot about how Iran and the Western powers have ended up in this quagmire. It represents another installment in what has become a drawn out maritime circus—involving drones, limpet mines, supertankers, and surveillance planes. Gliding gracefully through the Gulf of Oman, only to be unceremoniously apprehended, Stena Impero can tell us that there is more to a name than meets the eye.

Stena is a name that is derived from the Ancient Greek word ‘Stéphanos’, which in turn, derives from ‘stéph?’, meaning ‘to put round or to surround’. In ancient Greece, a wreath (symbolising a crown) was given to the winner of a contest. Impero denotes ‘empire’ in Latin. The name alone encapsulates everything that is anathema to the Iranian revolutionary elite.

Stena Impero, the ‘crown of imperialism’ as it were, is the unsinkable ship that buoys Iran’s deep-seated grievances towards the West. Her name, her apprehension, and the subsequent wrangling over culpability, is almost a perfect assemblage bearing all of the markings of the legacy of Iran’s troubled dialectic with Europe and the U.S. Let us venture beneath the tip of the iceberg.

The pattern of Iranian relations with the West until the 1979 Iranian revolution was weak dynasties succumbing to colonial pressures. This was how the Pahlavi dynasty was seen by the Iranian public as it consolidated its relationship with the United States in the post-World War II era. As an antidote, the father of the 1979 revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, conceived Iran’s revolutionary discourse by fusing Shia apocalypticism and revolutionary activism with a mixture of Third World-ism, anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, Islamic-Iranian utopianism, and notions of an eternal battle between justice and injustice.

Khomeini’s definition of Islam echoed the perceived struggle against colonial oppression: “Islam is the religion of those who desire freedom and independence. It is the school of those who struggle against imperialism.” This narrative informed the revolutionary mottos ‘Neither East nor West’ and ‘azadi, esteqlal, jomhuri Islami’ (‘freedom, independence, Islamic Republic’). Khomeini’s populist message to restore justice and integrity to Iran in the face of international and domestic humiliation resonated with a population that, despite the great oil boom of the 1970s, remained largely poor and rural.

The accumulation of revolutionary energy in the build-up to the Shah’s overthrow in 1979 can be attributed to Iran’s emancipatory aspirations vis à vis the West. While the Iranian protesters espoused diverse ideals, preferences, ambitions, and worldviews, there was one objective that was almost universal—and it was not only the fact that the shah had to go, but rather, wholesale opposition to political exploitation. There were those who wed this idea to a resistance to cultural capitulation, which had manifested during the shah’s state-imposed Westernisation campaign, a form of ‘modernisation without modernity.’ The shah’s acquiescence to what was perceived as foreign meddling and neocolonial subjugation had also contributed to a paradigmatic shift in Iranian political imagination amongst the Iranian intelligentsia and literati. Perceptions of the West as the bastion of democratic principles had faded and a new revolutionary discourse emerged calling for national independence and a return to Iranian-Islamic traditions.

This historical representation of the West is firmly built into the conceptual architecture of the regime, which portrays 1979 as a revolt in defence of national independence and political sovereignty. Anti-imperialism became the core pillar of Iran’s post-revolutionary episteme and foreign policy culture, informing and shaping its strategic preferences, priorities and preoccupations. So potent and commanding is this narrative that it is institutionalised in virtually every facet of Iran’s post-1979 political system, from its governing bodies to its vetting agencies, its security apparatus, and its religious bodies. It informs the country’s economic outlook, regional and foreign policy, and defines the boundaries of social and civil liberties. It buttresses national affinities and supports the psychological and political roots of the post-1979 national identity. It also provides the ideational and emotive canvas on which hegemonic emotions geared to nationalist activism are explored. This outlook serves to reinforce the principles behind the revolution, to galvanise society, and to ensure compliance and regime durability.

Thus, just as the toppling of the American-backed Shah was seen as national liberation, the seizure of the Stena Impero can be seen as an act of defiance and resistance against imperialism, which today manifests in the form of American hegemonic posturing in a world order that is characterized by hypocrisy and double standards, and where normative and security concerns have narrowed down to serve the interests of a chosen few. In this system, members of the Atlantic power constellation are subject to disciplinary and tutelary processes: as the British tanker tales attest, the UK is serving as a nodal point in Trump’s ‘maximum pressure’ crusade against Iran.

The seizure of the Stena Impero should be seen against this backdrop. In practical terms, Iran impounded the vessel as a ‘tit for tat’ response against what it perceived as an earlier John Bolton-inspired provocation in the form of the capture of the Grace 1. Symbolically, the figurative seizure of the ‘crown of imperialism’ represents Iran’s long and arduous struggle against foreign encroachment. Imperialism as we once knew it may be no more, but it exists in a reformulated version of its original goals. However, as always in international affairs, expansion or exertion of force or power stimulates resistance—and Iran is resisting. Until this dynamic is fundamentally altered, this pathology will not be expunged, and Iran and the West will remain firmly lodged in the choppy seas of conflict and crisis.

Ghoncheh Tazmini is a political scientist. She is the author of Khatami’s Iran: the Islamic Republic and the Turbulent Path to Reform (I. B. Tauris, 2009) and Revolution and Reform in Russia and Iran: Politics and Modernisation in Post-Revolutionary States (I. B. Tauris, 2012). She is an Associate Member of the Centre for Iranian Studies at SOAS, and Research Associate at ISCTE-Center for International Studies, University of Lisbon, Portugal. As a British Academy grant-holder, she is currently carrying out research on a Global History of Iran and Portugal in Hormuz in the 16th and 17th centuries.

No comments:

Post a Comment