The War Powers Act, which once was approved by the Congress to mandate the president to get authorization to launch military operation overseas, can be easily regarded as an unconstitutional encroachment on executive power by the U.S. president under the pretext of protecting national interest.

Jim Bovard, an anti-war American author whose articles have been publicly denounced by the chief of the FBI, the Postmaster-General, the Secretary of HUD, and the heads of the DEA, FEMA, and EEOC and numerous federal agencies, has explained in his article published by the Libertarian Institute that the Congress' War Powers Act has failed to deter U.S. attacks abroad in the subsequent decades.

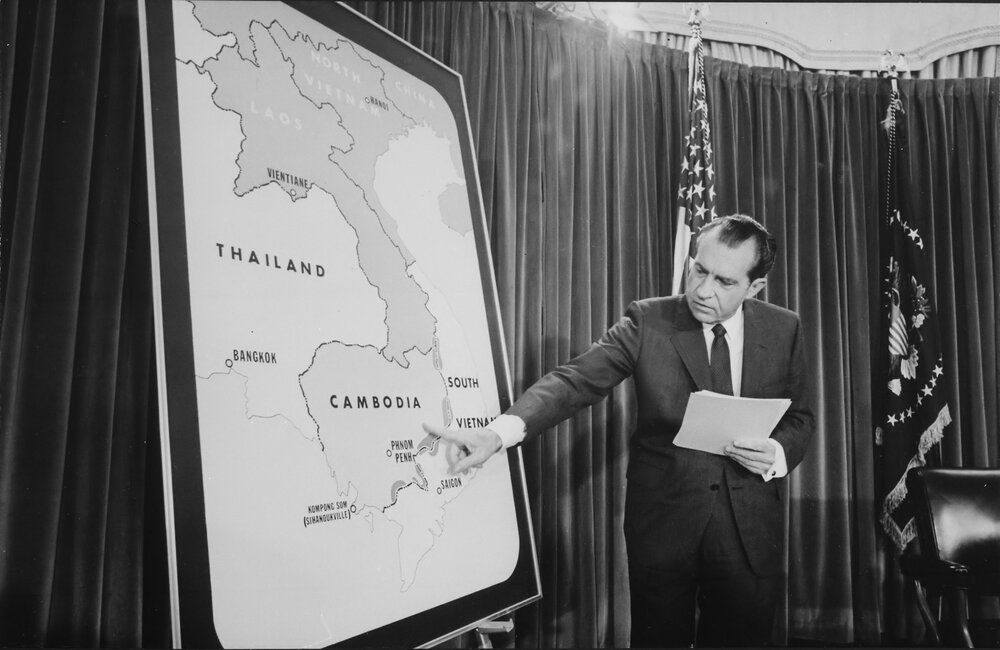

Fifty years ago, President Richard Nixon popped up on national television on a Thursday night to proudly announce that he invaded Cambodia. At that time, Nixon was selling himself as a peacemaker, promising to withdraw U.S. troops from the Vietnam War. But after the sixth time that Nixon watched the movie “Patton,” he was overwhelmed by martial fervor and could not resist sending U.S. troops crashing into another nation.

Presidents had announced military action prior to Nixon’s Cambodia surprise but there was a surreal element to Nixon’s declaration that helped launch a new era of presidential grandstanding. Ever since then, presidents have routinely gone on television to announce foreign attacks that almost always provoke widespread applause—at least initially.

Back in 1970, congressional Democrats were outraged and denounced Nixon for launching an illegal war. In his televised speech, Nixon also warned that “the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world.” Four days after Nixon’s speech, Ohio National Guard troops suppressed the anarchist threat by gunning down thirteen antiwar protestors and bystanders on the campus of Kent State University, leaving four students dead.

Three years after Nixon’s surprise invasion, Congress passed the War Powers Act which required the president to get authorization from Congress after committing U.S. troops to any combat situation that lasted more than 60 days. Congress was seeking to check out-of-control presidential war-making. But the law has failed to deter U.S. attacks abroad in the subsequent decades.

In 1998, President Bill Clinton launched a missile strike against Sudan after U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania were bombed by militants. The U.S. government never produced any evidence linking the targets in Sudan to the terrorist attacks. The owners of the El-Shifa Pharmaceutical Industries plant—the largest pharmaceutical factory in East Africa—sued for compensation after Clinton’s attack demolished their facility. Eleven years later, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit effectively dismissed the case, “President Clinton, in his capacity as commander in chief, fired missiles at a target of his choosing to pursue a military objective he had determined was in the national interest. Under the Constitution, this decision is immune from judicial review.” Presidential determinations based on a secret (and often false) information were sufficient to legally absolve any killings or calamities abroad.

In 1999, Clinton unilaterally attacked Serbia, killing up to 1,500 Serb civilians in a 78-day bombing campaign justified to force the Serb government to embrace human rights and ethnic tolerance. Serbia had taken no aggression against the United States, but that did not deter Clinton from bombing Serb marketplaces, hospitals, factories, bridges, and the nation’s largest television station (which was supposedly guilty of broadcasting anti-NATO propaganda). The House of Representatives took a vote and failed to support Clinton’s war effort, and 31 congressmen sued Clinton for violating the War Powers Act. A federal judge dismissed the lawsuit after deciding that the congressmen did not have legal standing to sue. Most of the U.S. media ignored dead Serb women and children and instead portrayed the bombing as a triumph of American benevolence.

After the 9/11 attacks, President George W. Bush acted entitled to attack anywhere to “rid the world of evil.” Congress speedily passed an Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) which the Bush administration and subsequent presidents have asserted authorizes U.S. attacks on bad guys on any square mile on earth. Congressional and judicial restraints on Bush administration killing and torturing were practically nonexistent.

Bush’s excesses spurred a brief resurgence of antiwar protests which largely vanished after the election of President Barack Obama, who quickly received a Nobel Peace Prize after taking office. That honorific did not dissuade Obama from bombing seven nations, often based on secret evidence accompanied by false denials of the civilian casualties inflicted by American bombings of weddings and other bad photo ops.

In 2011, Obama decided to bomb Libya because the U.S. disapproved of its ruler, Muammar Gaddafi. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton notified Congress that the White House “would forge ahead with military action in Libya even if Congress passed a resolution constraining the mission.” Plagiarizing the Bush administration, the Obama administration indicated that congressional restraints would be “an unconstitutional encroachment on executive power.” Obama “had the constitutional authority” to attack Libya “because he could reasonably determine that such use of force was in the national interest,” according to the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel. Yale professor Bruce Ackerman lamented that “history will say that the War Powers Act was condemned to a quiet death by a president who had solemnly pledged, on the campaign trail, to put an end to indiscriminate warmaking.”

On the campaign trail in 2016, Donald Trump denounced his opponent as “Trigger Happy Hillary” for her enthusiasm for foreign warring. But shortly after taking office, Trump reaped his greatest inside-the-Beltway applause for launching cruise missile strikes against the Syrian government after allegations the Assad government had used chemical weapons.

The following year, the Trump administration joined France and Britain in bombing Syria after another alleged chemical weapons attack. Several officials with the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons leaked information showing that the chemical weapons accusations against the Syria government were false or contrived but that was irrelevant to the legality of the U.S. attack.

Why? Because the Justice Department ruled that President Trump could “lawfully” attack Syria “because he had reasonably determined that the use of force would be in the national interest.” That legal vindication for attacking Syria cited a Justice Department analysis on Cambodia from 1970 that stated that presidents could engage U.S. forces in hostilities abroad based on a “long continued practice on the part of the Executive, acquiesced in by the Congress.” The Justice Department stressed that “no U.S. airplanes crossed into Syrian air-space” and that “the actual attack lasted only a few minutes.” So the bombs didn’t count? If a foreign government used the same argument to shrug off a few missiles launched at Washington D.C., no one in America would be swayed that the foreign regime had not committed an act of war. But it’s different when the U.S. president orders killings.

In the decades since Nixon’s Cambodia speech, presidents have avoided repeating his reference to America being perceived as “a pitiful, helpless giant.” But too many presidents have repeated his refrain that failing to bomb abroad would mean that “our will and character” were tested and failed. Unfortunately, the anniversary of Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia passed with little or no recognition that the unchecked power of American presidents remains a grave threat to world peace.

No comments:

Post a Comment