TEHRAN – Thanks to the shifting of sand dunes, foundations of forgotten buildings and relics across the globe are uncovered time after time.

One of such historical gems is Dahane-ye Gholaman, or, according to German scholar of Persian and Elamite studies Walther Hinz, “Gateway of the Slaves.”

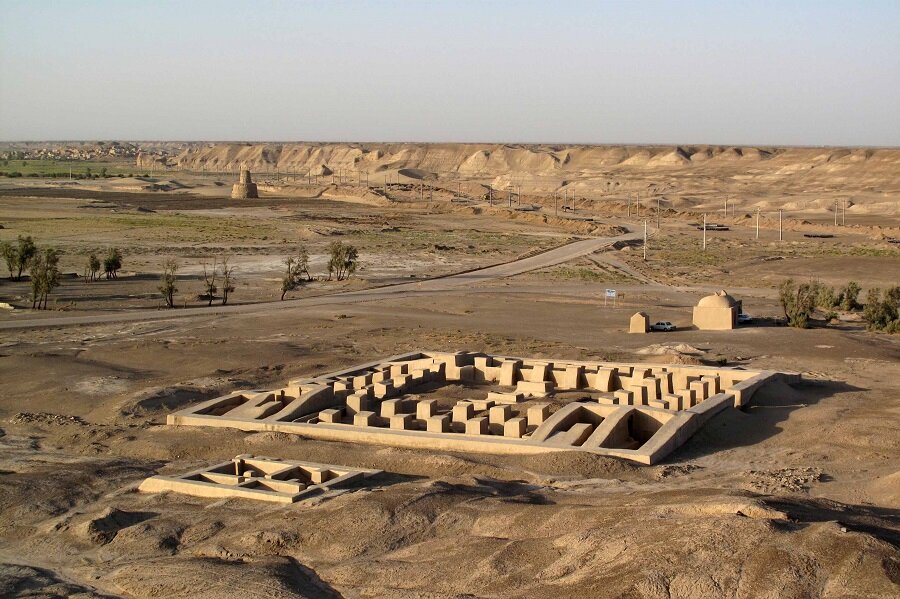

The archeological site, which was discovered in 1960 by Umberto Scerrato of the Italian archeological mission, is situated on a terrace at the foot of the desert plateau that surrounds the Hamun-e Helmand basin, near an artificial corridor that serves as the entrance into the basin and for which the site is named.

The site is located some two km straight south of the village of Qal’a-ye Now (“New fortress”) ca. 30 km southeast of Zabol in Sistan-Baluchestan province.

That this vast depression, though scoured by wind and choked with sand, was formerly fertile and inhabited is clear from traces of villages and agricultural works discovered in 1964.

According to the Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies, the excavations, directed by Scerrato, were begun in 1962 and continued to the end of 1966 under the sponsorship of the Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente (IsMEO). They revealed an urban settlement of considerable proportions, certainly far more extensive than the architectural remains that have been uncovered. It is a unique survival from the Achaemenid period and is notable not only for its size but also for its internal differentiation by function, reflected in the presence of large public buildings and an extensive residential area.

It is thus by far the most significant example of a provincial capital located at a distance from the imperial center. The other Achaemenid settlement of the region, which is located in the eastern, Afghan part of the province and was excavated by Roman Ghirshman, did not share the same characteristics, though the comparative study of the ceramics from the two sites does reveal some obvious similarities.

The dimensions of the inhabited area that have been uncovered are noteworthy: a length of 1.5 km from east to west and a width of 300-800 m. Archeological investigations have revealed that the city was established according to a generally unified plan and also have made it possible to identify at least two principal phases of construction. The excavated buildings, constructed of mud brick and pisé on a flat terrace below the desert floor, are distinguished by an absence of stratigraphy.

The entire complex suggests an urban foundation laid out according to a well-defined plan and literally built in the wilderness, inhabited for a brief period (a century or a century and a half), and then abandoned as a result of the natural forces that have always determined the survival and migration of urban settlements in the arid regions of Sistan: the instability of the delta and the inevitable resulting shifts in the system of irrigation channels, the sometimes disastrous flooding of the Helmand, and the salinization of the soil.

In particular, some minor fluctuations of the deltaic system are attested from the beginning of the sub-Atlantic phase (ca. 500 BC): “[T]he water input must have been reduced and channeled through the actual delta, possibly one of the reasons why the Achaemenian settlement of Dahane-ye Gholaman was abandoned.”

The residential quarter, which seems to have ex tended over about 100 ha, is divided into two parts by a spur of the terrace. On the western side the buildings are aligned along an ancient canal, the course of which can still be traced; it must have intersected another canal running north-south, dividing the eastern part of the town.

On the south at the eastern end of the excavated area, not far from the artificial corridor for which the site is named, stands a sort of massive natural tower called Qabr-e Zardosht (“Tomb of Zoroaster”), with a rectangular room hollowed out of its interior, now lacking its southern side.

A combination of excavation and surface survey permitted recovery of the plans of seven large structures, each with a large central courtyard, sometimes with porticoes, as well as several residential quarters in which the standard plan was that of a closed quadrangle without courtyard but with a corridor around a central square or circular structure in which there were several additional small rooms.

Dahane-ye Gholaman, was in all probability the capital founded by the Persians when they first settled in the region of Hamun-e Helmand: the Zarin of the earliest Achaemenid period.

As for the importance of Dahane-ye Gholaman for the history of Achaemenid Persia, it can be said that it is the sole large provincial capital surviving from the empire and that excavations there have brought to light a combination of “imperial” elements, identified in the public buildings, and local elements, noticeable especially in the valuable documentation of domestic architecture.

Together these elements, both unique and distinctive, ensure the fundamental importance of the site for understanding the origins and evolution of urban settlement on the Persian plateau in the Achaemenid period.

Recovered archaeological records and evidence, including residential, public, and administrative-religious structures, indicate pre-planned and intense urbanization. Unfortunately, the pottery from Dahane-ye Gholaman has not been paid the attention it is due, even though pottery from the site has been studied.

The studies show that innovation and demands on the pottery industry created local types of beakers, jars, jugs, and bowls and so on. Research on the pottery characteristics shows that the potters of this site were skilled in controlling the kiln temperature and were able to produce high quality wares, while various forms were commonly in use at the site.

Why Dahane-ye Gholaman?

As mentioned before, the Persian word “Gholam” translates to “slave”. Also, “Dahane-ye” means “a strait” so that, according to narratives, the town was called Dahane-ye Gholaman because of being in the vicinity of a natural strait of the same name where slave traders imported African slaves.

What is the best time to go?

Sistan-Baluchestan province has typically a hot and dry climate. The best time to visit the Dahane-ye Gholaman in terms of weather is from late February until late April, and late October until early December. During this period the weather is quite mild, with an average temperature of around 21 degrees Celsius. In these months the temperature does not exceed 24 ° C.

No comments:

Post a Comment