By Michael Jansen

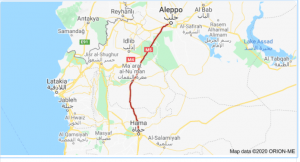

As soon as the Syrian government announced that the north-south highway was open last weekend, my courageous friend Jamil drove from Damascus to Aleppo and back. “The road was fine and very quick,” he told me on the phone on his return to the capital. The Hama-Idlib-Aleppo sector of the highway, the M5, is known as the “international road” because it begins on the Jordanian border and runs to the Turkish border. The highway was closed by conflict for eight years, forcing travellers to take a detour in the desert over rough roads. This route was 90 kilometres longer than the M5 and consumed six hours rather than four and a half, as well as more petrol.

The return of the M5 should lower costs of shipments of goods between Aleppo and Hama, Homs and Damascus at a time the Syrian economy is in crisis due to nearly nine years of warfare and US and European sanctions. Jamil’s journey shows that travel has been eased for civilians who save time as well as rationed petrol.

The capture of the M5 by the Syrian army is one of the most celebrated prizes in Damascus’ campaign to regain territory lost to takfiris and rebels since unrest erupted in 2011. The 450-kilometre M5 links Syria’s main cities, Deraa, Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo, and was the main artery for both commercial and personal travel before the war. The government began to lose control of the highway when diverse rebel and takfiri groups seized different sectors.

Before the war, the highway carried on a daily basis $25-million-worth of commercial traffic to and from Aleppo and Homs, the country’s chief industrial hubs. Syria’s cotton, grain, pharmaceuticals and export goods travelled along this route, which passes through the rich pistachio-growing region north of Hama and the now devastated towns of Khan Shaikhoun, visited by this correspondent in early September, Maarat Al Numan and Saraqeb, where the M5 meets the M4, the main highway from Aleppo to the port of Latakia on the coast. The western sector of the M4 is the next objective of the Syrian army and its Russian ally as it is the main route for raw material imports and exports.

After government forces recaptured takfiri-held Eastern Ghouta and areas in Deraa province in 2018, the army prepared for the long-awaited campaign in Idlib, the final bastion of anti-government takfiri and Turkish-sponsored militias. However, under Turkish and Russian pressure, this was postponed due to the presence of three million civilians, half of them displaced from elsewhere, amongst thousands of anti-government fighters.

Idlib province and adjacent slices of Hama, Aleppo and Latakia provinces were declared a “de-confliction zone”. A ceasefire was meant to be imposed and the M5 and M4 highways were to open and be put under the protection of Russia and Turkey. A 15-20 kilometre buffer zone was to be established around the “deconfliction” area, from which takfiris and heavy arms were to be excluded. Turkey was permitted to plant 12 “observation posts” in the “de-confliction zone” to monitor the ceasefire. Ankara was also tasked with separating takfiris from “rebels” (although there was no real difference) and disarming and isolating the takfiris. Turkish and Russian military police were supposed to patrol the area.

There was no ceasefire because the leading takfiri group, Al Qaeda-affiliated Ha’yat Tahrir Al Sham, and its allies refused to halt anti-government operations. Since they have been branded “terrorists” by the UN, they have been formally excluded from the ceasefire and continued to mount attacks on Syrian soldiers and civilians.

Since Idlib never became a “de-confliction zone”, the Syrian army launched its delayed offensive in 2019, seizing Khan Shaikhoun in late August, pausing to see what would happen, and then in December resuming its advance along the M5 to Aleppo. During the M5 campaign, the Syrian army had the full support of Russian air power and the backing of Iran-deployed Shia militiamen.

It is significant that the Russian military, as well as the Syrian Transport Ministry, simultaneously announced the M5 victory, making it clear that Moscow was prepared to defend the M5 highway and, perhaps, the M4, if and when the Syrian army manages to capture the western sectors of this strategic asset.

Last December, the Syrian army took control of the eastern sector of the M4 which links Aleppo in the north-west to Qamishli in the north-east. The Syrian army’s advance along this route appears to have been agreed between Russia, Turkey, the US and the Syrian Kurds. Since taking up positions, the army has not only regained Syrian territory, but has also acted as a buffer force between Turkish and Kurdish fighters.

Following Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw US troops deployed with the Kurds, the Turkish army and client militiamen seized from the Kurds a 120-kilometre stretch of territory south of the Turkish-Syrian border. This created a casus belli for the Kurds who were determined to recapture territory lost, or granted by Trump, to Turkey.

Although the US declared a troop withdrawal from Syria, up to 600 US soldiers remain in the northeast, allegedly, to protect the oil fields. The US troops, however, have also interfered with Russian military police patrolling the M4 near Qamishli, risking clashes and creating instability in an already unstable region of Syria.

No comments:

Post a Comment