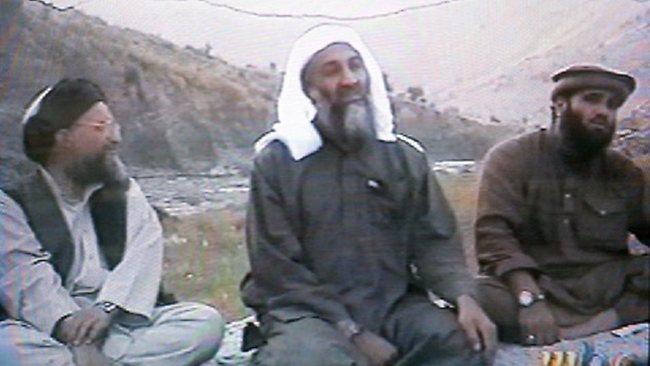

Al-Qaeda leaders Ayman al-Zawahri, Osama bin Laden and Suleiman Abu Ghaith in 2002.

by Peter Ford

What blasphemy is this? al-Qaeda has won? Absurd!

Most observers would say reflexively that, eighteen years after 9/11, the U.S. has cut al-Qaeda down to size, and if it has not quelled it altogether the remaining operations against Osama bin Laden’s organisation—such as the strike on al-Qaeda in Syria in Idlib on 31 August—amount to not much more than mopping up. But is this not a superficial reading of the situation?

Until Trump nixed the deal (temporarily?) the anniversary of 9/11 was set to coincide with an agreement between the U.S. and the Taliban, whereby the U.S. would withdraw from Afghanistan in return for assurances that U.S. troops will not be attacked as they leave and that the Taliban will not support groups such as al-Qaeda. Much of the discussion on the putative deal revolves around the question of whether the Taliban will respect any assurances they give.

But there is a deeper question here: the Taliban may or may not attack U.S. troops, but why would al-Qaeda today even want to attack the U.S. from Afghanistan? Or from anywhere at all? Has the U.S. not ended up aligning itself with al-Qaeda on the causes closest to al-Qaeda’s heart?

A Convergence of Interests

And what causes might those be? Leave aside the cause of besting its rival, the Islamic State (IS or ISIS), although the U.S. has done al-Qaeda an immense if unintended favour by largely removing from the scene al-Qaeda’s biggest competitor for recruits and funding. More to the point, how about the causes of fighting Iran, the Shia, the Syrian government, Hezbollah, and the Houthis, and generally making the Middle East safe for Sunni extremism?

‘Iran is the number one nation of terror’: has Donald Trump with this mantra not shifted the spotlight off Sunni terrorism, the undisputed bugbear of the U.S. in the first ten years after 9/11? And has al-Qaeda on its side not lost much of its anti-Western focus and become principally concerned with what it sees as heresy within Islam in the shape of Shiism and its offshoots?

Look at the absence of al-Qaeda reaction to the recent announcement that in light of the Iranian ‘threat’ the U.S. would be stationing troops once again in Saudi Arabia. Such stationing was an important catalyst for Bin Laden’s movement when, in the run up to and aftermath of the first U.S. war on Iraq in 1991, the U.S. kept thousands of troops in the holy land of Islam, considered anathema by many Muslims at the time. Now the prospect arouses barely a peep, so conditioned have the Saudi people and Sunnis generally become to seeing Iran as the enemy, not Israel or its protector the U.S.

Not that al-Qaeda ever appeared to care much about Israel’s misdeeds, at least to judge by actions rather than words. When did al-Qaeda ever mount a significant attack against Israel? So much fulmination, so little action. Even action against the U.S.: what did al-Qaeda do against the U.S. after the big coup of 9/11? It is necessary to go to the archives to come up with anything at all: the Times Square foiled car bomb attack in 2010 by a Pakistani who may or may not have been linked to al-Qaeda. The attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi in the confused aftermath of Muammar Gaddafi’s downfall in 2012 may also just count. Even taking into account a number of plots allegedly foiled by U.S. security agencies (often involving agents provocateurs), the record hardly amounts to strong evidence of a continuing major al-Qaeda targeting of the U.S.

The feeling, or quasi-indifference, appears to have been mutual. After the killing of Bin Laden in 2011 the U.S. seemed to act as though it believed that the account had been squared and there was not a lot of point in doing more than go through the motions on combatting al-Qaeda, especially with the appearance of the new kid on the terrorist block, IS, itself an offshoot of al-Qaeda in Iraq.

Allies in Syria and Beyond

The emerging convergence of interest between the U.S. and al-Qaeda has been most obvious in Syria. During the Obama years, the U.S. funnelled immense amounts of arms and equipment to jihadi groups in full knowledge that much of it was ending up in the hands of al-Qaeda affiliates, notably the group originally known as Jabhat Al Nusra. This group began life as al-Qaeda in Syria, before disagreements with al-Qaeda central led to a degree of distancing. With the passing years Nusra stepped up efforts to rebrand itself, first as Jabhat Fatah ash-Sham (JFS), then as Hayat Tahrir ash-Sham (HTS), its current avatar. But its basic radical jihadi ideology, and its oppressive sharia-inspired behaviour in areas it controlled, never changed.

The U.S., by mobilising all the immense means at its command to weaken and attempt to overthrow Bashar al-Assad, did much of the work of Nusra/JFS/HTS for it. The U.S. still does that, without ever manifesting the slightest concern that removing Assad would inevitably pave the way to jihadi control over all Syria. For if the U.S. no longer finds it expedient to pour arms directly into the maw of jihadi groups, it lifts not a finger to prevent ally Turkey from doing so with advanced U.S.-supplied weaponry, or Qatar from channelling copious funding to those groups. It constantly admonishes, with threats, the Syrian government and the Russians for using much the same level and type of military effort to dislodge HTS from Idlib that the U.S. itself used in Coalition operations to remove IS from Mosul, Fallujah, and Raqqa. At one point in 2018 it threatened to bomb Syria if Assad’s attempts to recover Idlib were not halted, prompting barbed comments that the U.S. Air Force, which had already bombed Syrian targets twice—in 2017 and 2018—was acting as the al-Qaeda air wing.

U.S. officials have put considerable effort into attempting to hobble Assad and the Syrian Arab Army in what they call their war on terrorism by imposing sanctions, withholding international reconstruction assistance, and pressuring countries not to normalise relations with Syria. It lionises groups like the White Helmets, considered by the Syrian government and Russia to be auxiliaries of HTS. It encourages think tanks hostile to Syria and Russia and does everything in its power to shape a mainstream media narrative on Syria that can only give comfort to a group, HTS, which plays adroitly on Western consciences in the hope that assistance from the West will continue and possibly even develop into armed intervention.

True, the U.S. continues to pay lip service to the cause of fighting al-Qaeda and even occasionally mounts some token military action against it, as when on 30 June this year the USAF launched a strike on a location near Idlib where commanders of an al-Qaeda affiliate, Hurras al-Din (the Guardians of Religion), were gathering. The Pentagon claimed that the purpose of the strike was to pre-empt ‘external’ attacks, which would endanger ‘U.S. citizens, our partners, and civilians’. The main impact of this curious attack out of the blue, following two years of complete U.S. inaction against al-Qaeda in Syria, was to deflate an emerging clamour for U.S. intervention in Syria, and may have been a Pentagon power play against ultra hawk John Bolton. The U.S. carried out an almost identical strike on 31 August, which is likely to strengthen the hold of HTS, left unscathed, over Hurras al-Din and other unruly factions that are more brazen in their al-Qaeda affiliation. Even if the two strikes are taken entirely at face value their rarity underlines that if the U.S. seriously wished to oppose al-Qaeda, it could and would be bombing HTS and its allies regularly. It can only be assumed that the U.S. broadly prioritises undermining Assad and Iran over the fight against Sunni terrorists, who for their part—especially now with IS a spent force—no longer have much appetite or incentive for attacking the U.S.

The de facto convergence between the U.S. and al-Qaeda is equally obvious in Yemen, where the U.S. is propping up the Saudi-led military coalition in its efforts to remove the Houthi-controlled government, deemed over-reliant on Iran. The U.S.-Saudi intervention has led to a chaotic situation where al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula has gathered considerable strength.

U.S. rhetorical support for the Uighurs (to spite China) and military cooperation with predominantly Muslim Azerbaijan, from which Israeli drone attacks on pro-Iranian forces in Iraq have reportedly been launched, may also not be seen with disfavour by al Qaeda, jihadi ranks in Syria being full of Uighurs and Caucasus Muslims.

Repeating the Past

We have seen this movie before, of course. U.S. support for Afghan mujahideen fighting Russia helped create the conditions for the emergence of al-Qaeda in that country in the first place, just as the overthrow of secular dictators in Iraq and Libya helped create the conditions for the emergence of IS and other jihadi groups in those countries.

At some subliminal level, the architects of U.S. Middle East policy seem to recognise that they have a problem with pretending that Iran has overtaken al-Qaeda or al-Qaeda-inspired groups as terrorist-in-chief. Possibly for this reason, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has tried to smear Iran as a secret supporter of al-Qaeda, a claim no honest observer can possibly take seriously.

At all events, the question today—18 years after 9/11—is whether the U.S. obsession with Iran will not backfire like previous misadventures and play once again into the hands of Sunni extremists, inheritors of the Bin Laden legacy. We shall see the answer to that if U.S. Syria policy succeeds, and an economically crippled and politically fragmented Syria becomes once more ungovernable, with Assad forced out of power—an outcome for which al-Qaeda must be fervently praying.

Peter Ford is an expert on the Middle East. An Arabist, he served as British Ambassador to Syria and Bahrain before joining the UN to work on refugee issues.

No comments:

Post a Comment