Alex Shams

All photos taken by author.

Welcome to Muscat, the capital of Oman, where the Arab World meets the Indian Ocean. Due to centuries of Omani seafaring, empire, and trade, Muscat is today a spectacularly diverse port town that looks more to the seas east, north, and south for inspiration rather than to the barren flats and scraggy mountains of the Arabian Peninsula to the west. Oman is a kaleidoscope of Indian Ocean worlds, connected to Sindh, Zanzibar, Baluchistan, Iran, and Yemen just as much as it is to the Arab world, and it’s not afraid to admit it.

While in the other Arab countries of the Persian Gulf ethnic diversity has often been downplayed in favor of a unitary Arab identity, in Muscat, the multilayered heritage of the past – and the way it has shaped the city’s present – is celebrated and remains an undeniable part of contemporary urban life.

The Hidden Port

Muscat was known by the ancient Greeks as Cryptus Portus, “the hidden port”, as it is sheltered from the sea by towering rocky mountains. This makes the harbour easy to defend – and a perfect hideout for pirates. After a brief period of Sassanian Persian rule, the interior fell to the Abbasids with the arrival of Islam in the 700s.

Before the Abbasids, much of Oman spoke southern Arabian languages distinct from Arabic. Many of these, like Mehri, are still spoken in Oman’s south. Port towns like Muscat, however, maintained a great deal of independence from the interior. Historically, “Oman” only referred to the interior region; Muscat was the name of both the city and the coast around it. This changed in 1970, when the whole country was renamed Oman.

Muscat prospered as a result of its coastal location, becoming a central node on trade networks that crisscrossed the Indian Ocean, bringing goods like spices, ivory, cloves, wood for ship-building, and fruits as well as slaves from such far-flung places as Mozambique, Indonesia, Kerala, Iraq, Baluchistan, and Sudan. These networks also facilitated the exchange of knowledge, education, and religion across vast distances. Port cities became cultural entrepots, with merchants settling across the Indian Ocean and sending brothers, cousins, and friends to far-off places to build new contacts and connections. Indian mango pickles traveled to Iraq, African culture reached Iran, and Baghdadi synagogues and Syriac churches found their way to India. Sailing the monsoon winds, traders from Oman put down roots in Surat, Zanzibar, and Malacca, while Muscat became home to traders from South Asia and East Africa.

Land and Sea

Today, it is common to think of geography and region in terms of land. Looking at a map, one could be forgiven for thinking that because Oman is next to Saudi Arabia, they must be culturally or socially connected. Even the basic building blocks of geographic categorization – like regions and continents – refer to land masses. This is true even when that land is composed of deserts and mountains across which movement is nearly impossible. Maps, which emphasize politically-demarcated borders, push us to see nation states and military control – rather than mobility and topography, more important for exchange. The ocean is imagined as a barrier.

But historically water travel has been quicker and cheaper than land travel. Muscat, like all port cities, is a place defined by its water connections. Until the 20th century, it took weeks of extremely difficult and dangerous travel overland to go from Muscat to Oman’s interior – much less to modern Saudi Arabia, past hundreds of miles of desert. The water routes that connected Muscat north to Persia or east to India, in contrast, were easier – and the places they reached wealthier and more interesting.

Muscat – and the Indian Ocean world it reveals – highlights how our conception of geography defined by land is deeply ahistorical. It is only since the early 1900s, when train tracks were laid and modern states invested heavily in road infrastructure – and had no qualms about bulldozing natural wonders like mountains and rocks to build highways – that buses and cars became feasible modes of travel. For millennia, Muscat was much closer to India, Persia, and East Africa than it was to inland Arabia. And it was these connections that sustained it.

Oceanic Cultures

In the early 1500s, the nature of Indian Ocean trade networks changed dramatically. Previously, no single power dominated the trade, defined by close networks of traders and port cities that were independent but interconnected. Portuguese warships, however, entered the Indian Ocean with a mission: to monopolize Persian Gulf and Red Sea trade by controlling strategic ports and preventing local mercantile activity, imposing control over every corner of the region. Along the way, they seized Muscat, before conquering Goa and Kerala, where they put Muslims and Jews to the sword, imposing a second “Inquisition” resembling the Reconquista slaughter and expulsion of non-Christians back in Iberia.

The Muscat coast was taken by the Portuguese. But the Omani interior remained relatively isolated. After a century of Portuguese rule in the Persian Gulf, the Ya’ariba dynasty emerged and – with the help of the Persians and Baluch – expelled the colonizers. They launched a war across the Indian Ocean, attacking Portuguese ports in Zanzibar, Mombasa, and Gujarat, in the process building an Omani maritime empire with Muscat at its heart.

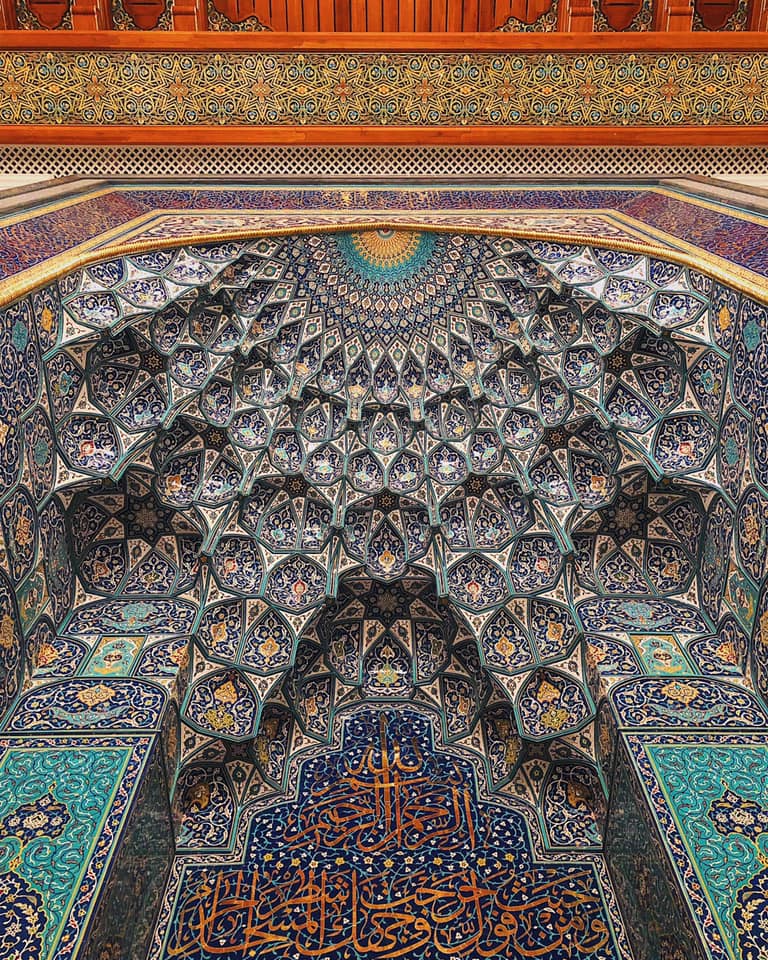

Muscat rebuilt its oceanic connections, deepening and strengthening commercial ties with ports across the Indian Ocean. It also began developing its own empire. Traders returned to Muscat. Among the most well-known trading community in Muscat are the Lawatis, who settled in a walled neighborhood called Sur al-Lawatiya in the 1700s. Lawatis were Sindhi merchants speaking a language called Lawati (Khojki), based on Sindhi but freely mixed with Arabic, Persian, and Hindi. Originally Khoja Ismaili Muslims, they converted to Shia Islam after arriving in Muscat. They maintain the major Shia mosque that defines Muscat’s seaside promenade today.

Beside the Lawatiya, thousands of Persians also made their homes in Muscat and neighboring port towns. As in other Persian Gulf countries, these Persian traders and their descendants are called Ajam. The Ajam hail from southern Iran, especially towns around Shiraz and port cities like Bandar Abbas. Some were originally Arabic-speaking – from Iran’s Arab communities – and many were Afro-Iranians, though Persian was also widely spoken. One of Oman’s languages, Kumzari, is a mixture of Persian, Arabic, and Portuguese – a port language that emerged as a way for traders in the Persian Gulf to understand each other in the 1600s.

Also hailing from the coasts of the Persian Gulf are the Baharna, Bahraini-origin traders. Bahrain was ruled by Oman during the 1700s, after seizing it from Safavid control. The Baharna maintain a Shia matam (hosseiniya) directly beside Muscat palace, a statement of their close relations to the crown.

Since at least the 1600s, Oman maintained close relations with Baluch leaders just across the Arabian Sea, and many local Baluch rulers – called meer – pledged loyalty to the Sultan. For a time, Oman’s empire even extended into Baluchistan, where the port cities of Chabahar (in modern-day Iran) and Gwadar (in modern-day Pakistan) became a key hub for Oman’s trading and maritime fleets.

Thousands of Baluch moved to Muscat and around the Gulf, some serving as soldiers in the Sultan’s army and others working as traders. Today perhaps one out of every 5 Omanis is of Baluch origin, and the Baluchi language is widely spoken.

In the early 1800s, Muscat was controlled by Said bin Sultan, who in 1833 established Zanzibar as Muscat’s second capital to manage the trade between the two. In comparison to Muscat, which had fallen into relative poverty as the British, French, and Dutch replaced the Portuguese in monopolizing oceanic trade, Zanzibar was the wealthy jewel of Oman’s empire. Oman’s sultan continued and deepened Portuguese colonial policies, expanding the slave trade and the plantation economy, in the process dispossessing indigenous people of farm land. In the decades that followed the royal court’s move, thousands of Omanis left Arabia’s shores for Africa’s coast. They docked at Stone Town, Zanzibar’s main city. Many moved into the interior over time, spreading across East Africa – modern Tanzania, Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, and Congo – and working as traders, using their connections to the ports to distribute goods inland.

Omani men learned Swahili and shed Arabic over time, marrying local women and building a hybrid culture. The word “Swahili” is actually an Arabic word – it comes from “Sawahel,” the “coasts,” and Swahili means “[language] of the coasts.” It’s a hybrid trading language that emerged from the interaction of Arab and Persian traders with locals. Persian influence in Zanzibar, specifically from Shiraz, was so strong that Persian New Year Nowruz is still celebrated today. (It was also celebrated until recently in Oman under the name “Mehrejaan”).

Returning and Remaking “Oman”

By the turn of the century, after East Africa fell under German and British rule, Omanis stayed. Ironically, their presence was facilitated by colonial efforts to build trains and roads, allowing them to travel further distances more easily and transport port goods further than ever before. Like the Lebanese in West Africa and Indians in Uganda, Omanis in Zanzibar – which came to refer in Arabic to all of East Africa, despite differences between regions – were intermediaries between colonial authorities and locals.

The Omanis of Zanzibar only began returning to Muscat in the 1970s. This movement was triggered by nationalist revolutions in East Africa, especially in Zanzibar, where independence and the triumph of the Afro-Shirazi party was accompanied by massacres of Arabs and South Asians. This was combined with the discovery of oil back in Oman, which made “return” an attractive option. But many families could trace their roots in East Africa back four or five generations, and few Zanzibaris – as they came to be called by others back in Oman – spoke Arabic. Even today, tens of thousands of Zanzibaris in Oman speak Swahili at home, and they often maintain cultural differences based on their regions of origin in East and Central Africa.

Oman’s food culture is one place where this variety of influences can be seen today. Restaurants across the country serve dishes like biryani (Indian), mandi (Yemeni), and Mandazi (Zanzibari) as Omani food, highlighting how integrated these influences have become. For a sense of the diversity contained in a single meal, let’s deconstruct the following lunch served at a Swahili home in Muscat:

As British and French colonial authorities imposed their rule across the Middle East, East Africa and India, Muscat began to turn inwards. Sultan Said bin Teymour, who ruled from the 1930s to 1970, closed Oman from the world in fear of foreign intervention. He moved the court from Muscat to Dhofar. As Oman languished in isolation and poverty, Teymour became increasingly eccentric, banning cigarettes, imposing strict “no one outside after nightfall” rules, and refusing to build basic infrastructure like schools, electricity, and water.

All of this changed in 1970, when Sultan Qaboos overthrew his father and embarked on a modernization drive, fueled by recently discovered oil reserves. As nationalist governments took over decolonized East African states, tens of thousands of Omanis who traced their history in those countries fled, “returning” to Oman after generations in Zanzibar. While Oman was, until the 1970s, a patchwork of cities, provinces, and regions each with their own cultural diversities and mixtures, the modernization drive sought to unite them into a modern Omani national identity.

Omani, Arab, and What Else?

Similar to many other countries in the region, Oman today stresses an Arab identity. There is, however, a deeper apprehension about Arab nationalism, born both out of political exigency – a failed 1970s revolt against the Sultan was inspired by Arab nationalism – as well as a recognition of diversity as a natural component of national identity. This is exemplified in the national discourse of “tolerance,” which emphasizes Oman’s diversity and attributes it to the country’s unique history. But this not only risks whitewashing Oman’s history, it romanticizes the present. Muscat’s central role in the East African slave trade – or its monopolization of Zanzibar’s economy – is strenuously downplayed in the national narrative. And thousands of Zanzibari Omanis, for example, remain stateless in East Africa, prevented from return because they are unable to prove ties to their homeland.

With the arrival of modern systems of regulating international travel like passports and customs controls, its harder to maintain connections across the sea. It’s no longer possible for trading communities to pick up and settle elsewhere. Ruled by central government with different ideas about national identity, travel is easier – but far more regulated – than ever before. Today, when Middle Easterners and South or East Asians come to Muscat, they come on temporary contractual work visas. While they may seek to make a life in Oman, unlike those who came before the modern age, their stay will be temporary since Omani law largely prevents foreigners from acquiring nationality. Many of them will lack basic civil or labor rights – not unlike the thousands of enslaved people who passed through Muscat historically.

But for many Omanis, in their daily lives, there is little contradiction between the multiplicity of histories, identities, stories, and tastes that make up Oman. This vision of national culture comes together is at Omani restaurants: Biryani is Indian, but also Omani. Mandi is Yemeni, but also Omani. Ugali is Zanzibari, but also Omani. All of these dishes are served at an “Omani restaurant.” Instead of arguing whether they’re “Arab OR Phoenician,” “Arab OR Kurdish,” etc, in Oman, the question could be rephrased as, “Omani, Arab, and what else?”

This diversity is also visible in Omani Arabic, peppered with expressions from Persian, Swahili, and Urdu. In Muscat’s souq, you constantly hear “barabar,” meaning “perfect!” coming from “equal” in Urdu, and before that from Persian, where it means “together”. You’ll hear “khar, shakhsiya” coming from the Persian word “khar” خر for donkey. While in Persian, this word has a negative connotation, in Oman, it means a “strong personality”. Beyond this, words like umbar (storage), sida (straight ahead), makumsha (spoon), barasti (date-branch house), waZungu (white people), and many more point to origins across the sea.

Reminders of the ocean-faring past are still there, often revived in new ways. There are Baluchi families with branches in Muscat and Iran’s Chabahar that meet regularly for weddings, or Ajami who make frequent visits to Iran for pilgrimage or health tourism. There are the Lawatis who continue speaking a dialect of Sindhi, and the diverse array of clothes, food, and music on display at a typical Omani wedding. Muscat is still today defined by the sea.

Alex Shams

Alex Shams is an Editor at Ajam Media Collective. He is a writer and PhD student of Anthropology at the University of Chicago.

References

Adelkhah, Fariba. The Thousand and One Borders of Iran: Travel and Identity. Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2016.

Casey-Vine, Paula, ed. Oman in History. Immel Publishing, 1995.

Ho, Engseng. The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean. University of California Press, 2010.

Mirzai, Behnaz. A History of Slavery and Emancipation in Iran, 1800-1929. University of Texas Press, 2017.

Limbert, Mandana E. In the Time of Oil: Piety, Memory, and Social Life in an Omani Town. Stanford University Press, 2010.

Peterson, J.E. “Oman’s Diverse Society: Northern Oman,” Middle East Journal, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Winter, 2004), pp. 32-51. Tikriti, Abdel Razzaq. Monsoon Revolution: Republicans, Sultans, and Empires in Oman, 1965-1976. Oxford University Press, 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment