Ask anyone in France from an ethnic minority background when they first experienced a robust police document check and they will not say during the current coronavirus lockdown.

Most are brought up in the banlieues, on the fringes of major cities, on decrepit council estates where sinister state interference in day-to-day life remains the norm. Gratuitously violent restrictions on movement are all regularly deployed, and not just in times of crisis.

The kind of “controls” that we are now seeing during the health emergency start extremely early in life. You can always see people running away after the warning “Keufs” – Verlan street slang for police officers – is shouted out in the cités.

The jargon is contrôle au faciès – face control. Secular France is officially colour-blind, meaning that statistics about skin colour and racial or religious background are not compiled by officials. However, sociological studies routinely reveal scandalous discrimination against those with dark skin, who are stopped and brutalised the most.

Racial profiling is designed to demean – to create an underclass that is constantly under suspicion in a society full of extremely powerful bigots. At best, the checks are humiliating. At worst, they can and do end in a suspect being killed. This is why ethnic minority youths in particular try to get away.

All of this is worth considering at a time when the French authorities are imposing a minimum fine of €135 ($140) for anyone breaking the coronavirus lockdown. Those repeatedly caught without the right paperwork face six months in prison.

It is absolutely imperative that restrictions are enforced to stop the spread of the virus. If you have not got a valid reason for briefly leaving home – whether shopping for food or taking some exercise, for example – then you should not be exposing yourself, and potentially thousands of others, to COVID-19. That is why close to 14 million checks have been carried out so far.

Beyond such public health necessities, however, there is no excuse for the extreme discrimination that is going on in France right now. The repression that so many in the banlieues have always known is worsening as the coronavirus crisis highlights the inadequacies of a society that is supposed to be grounded in the most idealistic principles imaginable. The French Republic is meant to protect “Freedom, Equality and Fraternity” but it is failing miserably.

This came into sharp focus this week when riot police were deployed on a number of estates in the northern suburbs of Paris after a motorcyclist from an Arab Muslim background was critically injured by the door of a patrol car which was allegedly swung open deliberately in front of him while he was travelling at high speed through Villeneuve-la-Garenne.

Officers denied any wrongdoing, but the trouble that followed there and in other cités across France, led to a dozen of arrests including that of a French-Algerian journalist who was manhandled and handcuffed by police as he filmed them firing tear gas canisters at youths who were aiming fireworks at them.

In one of the most gravely disturbing incidents of recent days, police in the southern town of Béziers are facing criminal charges including manslaughter following their arrest of a 33-year-old father of three on 8 April.

Mohamed Gabsi, a Muslim from an Arab background, died in custody within an hour of being handcuffed and dragged into a patrol car. Apparently fit and healthy, Gabsi had lost consciousness during the trip to the police station after officers sat on his chest to restrain him, according to prosecutors.

[ ALERTE INFO ] Un sans domicile fixe âgée de 34 ans, est mort mercredi soir au commissariat de #Béziers, après un contrôle de police pour "non-respect du confinement et du couvre-feu" imposé dans la ville.

9,477 people are talking about this

Béziers, one of the most impoverished towns in France, has been described as a “Far Right Laboratory”. Its Mayor Robert Ménard – who is backed by the Rassemblement National, formerly the Front National – introduced a 9pm-5am curfew, and called for it to be policed with maximum force.

The initial arrest of Gabsi was recorded, as was that of a 21-year-old Muslim of North African origin on an estate in Les Ulis, in suburban Paris. The routine was chillingly familiar – the boyish Sofiane was held down, his wrists were handcuffed, and he then began screaming for help in a high-pitched voice.

When officers became aware that they were being watched, they took Sofiane to a nearby doorway to rough him up further. Sofiane was pummelled with truncheons and punches as he lay on the floor.

A “Triangle” violation is then said to have taken place – the term describes an intrusive pat down in the groin area. It is a procedure that on occasions amounts to sexual abuse. Extreme versions have included police forcing their telescopic truncheons inside their victims, leading to complaints of rape.

An officer wearing a balaclava put his hand on Sofiane’s mouth to stifle his shouts, and it is alleged that Sofiane bit him. In turn, Sofiane also claims that another officer trampled on his chest and threatened to take him to “the forest to burn” him. The entire incident is under criminal investigation.

Such abuse has been unrelenting. When the lockdown started in mid-March a whole squad of riot police was filmed pinning a black teenager on the floor in a Paris marketplace as her mother pleaded for mercy.

Interpellation D’une femme par les forces de l’ordre car elle avait pas l’attestation et elle refuse l amande !!#confinementjour2 #Confinementotal #COVID19 #Paris

3,244 people are talking about this

Another youth with the same racial profile was filmed collapsing after being pushed by police during a contrôle in the north-east suburb of Aubervilliers. A suspect from an Arab background was cooperating fully before he was kicked in the groin, and a clash between police and residents on an estate in Chanteloup-les-Vignes, north-east of Paris, meanwhile led to a five-year-old girl being hit in the head by a rubber “defensive bullet” from a police flashball gun (Lanceur de balles de défense).

Jeune fille de 18 ans, sortant faire des courses pour son enfant. Elle aurait été tasée. Elle avait son attestation et sa pièce d'identité. Vivement la lutte contre les virus dans la police.

Ça se passe à #Aubervilliers #violencespolicières @T_Bouhafs @davduf @CCastaner

1,023 people are talking about this

It was in Chanteloup-les-Vignes that “La Haine” (Hate), the classic 1995 movie focusing on discrimination against minorities was filmed. Ladj Ly’s “Les Misérables”, all about muscular policing in the suburbs, was this year nominated for an Oscar. There are very good reasons why artistic representations of the cheapness of life in the banlieues remain a key part of modern French culture.

Fines worth more than €120 million ($129.5 million) have been handed out to anyone caught on the street without the right documentation, and there is plenty to suggest that the poorest areas of France are being punished the hardest.

This applies to communities being decimated by the disease too. Stéphane Troussel, president of the General Council of Seine-Saint-Denis, the chronically underfunded department north-east of Paris, said the population there was “poorer and more fragile with a weaker health system”, and that “inequality kills”.

Meanwhile, the notoriously reactionary Paris Police Prefect, Didier Lallement, has already blamed the sick for their own misfortune, saying: “Those who find themselves in intensive care today are those who, at the beginning of confinement, did not respect it.”

Lallement has, following Interior Ministry advice, apologised for the outburst, but it says everything about a force that – from day one – has handled the COVID-19 pandemic as a crime emergency, rather than as a health one.

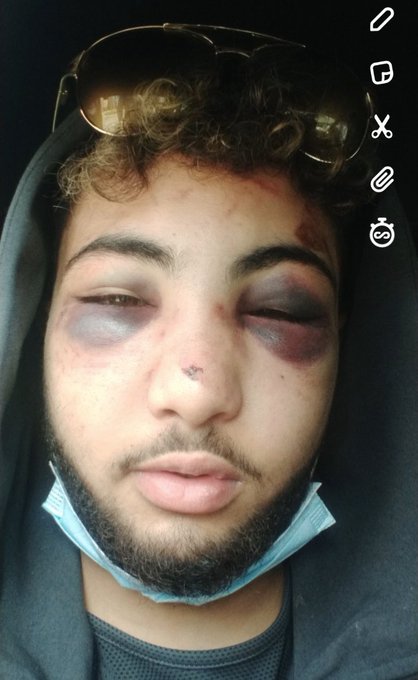

Other complaints against the police filed during the crisis are supported by photographs showing alleged victims with badly bruised faces and swollen eyes. The worst violence is said to take place inside police custody cells.

Violences policières, encore

Les Ulis, encore

Yassin, 30 ans, accuse des policiers de l’avoir passé à tabac le 23 mars 2020 alors qu’il sortait de chez lui

« Ici, les policiers sont déchaînés en ce moment. Ils ont fait ça à plusieurs personnes du quartier » dit-il.

[Thread] 1/

2,764 people are talking about this

« Doigts dans les yeux, coups de poing, coups de rangers dans la tête, insultes racistes » : Sofiane, 19 ans, a été tabassé par des policiers à Strasbourg, le 18 mars dernier. Les violences se sont poursuivies jusque dans le commissariat.

Une enquête a été ouverte.

[Thread] 1/

14.2K people are talking about this

Les violences policières, les bavures, c’est réel ! On vous apprend ça à l’école de police ?! #ViolencesPolicieres @BOUZROU1 @BelattarYassine

101 people are talking about this

« Espèce de sale bougnoule, tu vas crever aujourd’hui » : j’ai recueilli le témoignage de Mohamed, 26 ans, pompier volontaire, passé à tabac le 10 avril à St-Pierre-des-Corps.

10 jours d’ITT.

Un suivi psy.

Comme d’autres victimes de violences policières, il a déposé plainte.

2,592 people are talking about this

These kinds of attacks, which are aggravated by allegations of racial abuse, are institutionalised. They are a throwback to the days of French colonialism when a black African or Arab appearance was considered enough of an excuse for police brutality. This lingering reality has frequently persuaded tens of thousands to take to the streets to protest.

The last march I attended was in Paris in November last year when anger was high because a former Front National candidate had tried to burn down a mosque. Polls show that the party and its latest incarnation, the Rassemblement National, have always had massive support among police and soldiers.

Such forces of law and order are now notable by their absence in the upmarket residential squares and boulevards of Paris. There are hardly any police checks, while the big estates in Seine-Saint-Denis, which have three times less intensive care places than the capital’s hospitals, are swarming with patrols carrying out bureaucratic checks on ethnic minority communities.

The great fear is that this two-tier system – during a time of high tension – will have disastrous consequences. It was a contrôle au faciès that led to three weeks of rioting across France in 2005. The cités exploded after Zyed Benna, 15 and from a Tunisian background, and Bouna Traoré, 17 and from a family originally from Mali, died while hiding from police in an electricity sub-station in Clichy-sous-Bois, one of the most isolated of Paris’s suburbs. The innocent teenagers did not want to go through a contrôle and ran away.

Cités dwellers then wanted to highlight the profound malaise at the heart of society, using a traditional method of gaining attention that goes back to the French Revolution and before. The anarchy that followed was so intense that a state of emergency was declared on 9 November 2005 and curfews introduced.

Concern about social disorder is one of the reasons why 22 organisations, including Human Rights Watch, have called for an end to excessive police checks during the COVID-19 lockdown.

COVID-19 is already having a grave impact on the world in which we live. There are compelling comparisons to catalysts such as war and famine. Alterations to our economies, our politics and numerous other departments of life are guaranteed.

Social interactions – the way we relate to each other – are likely to undergo the biggest overhaul. In the case of the treatment of ethnic minorities in France, profound and radical change cannot come soon enough.

No comments:

Post a Comment