At more than 90 years old, Haj Farahat - pictured here in 2015 - is one of the very few remaining Palestinian refugees who fled to Egypt escaping the 1948 war (MEE/Ibrahim Ahmad)

In a conflict centred on the relationship between land and people, the issue of Palestinian refugees has been a sticking point in diplomatic efforts ever since the establishment of the state of Israel - and it seems that US President Donald Trump's so-called "deal of the century" is no exception to this rule.

Israelis and Palestinians have been at loggerheads over who is a refugee, what rights they are entitled to, and what their long-term fate should be, as countless attempts by the international community to reach a consensus on the issue have failed.

The latest bid, this time by the Trump administration, seems not only geared to fail just as past negotiations have, but appears to be founded on an attempt to be to do away with the very issue of refugees altogether.

Millions scattered across the region

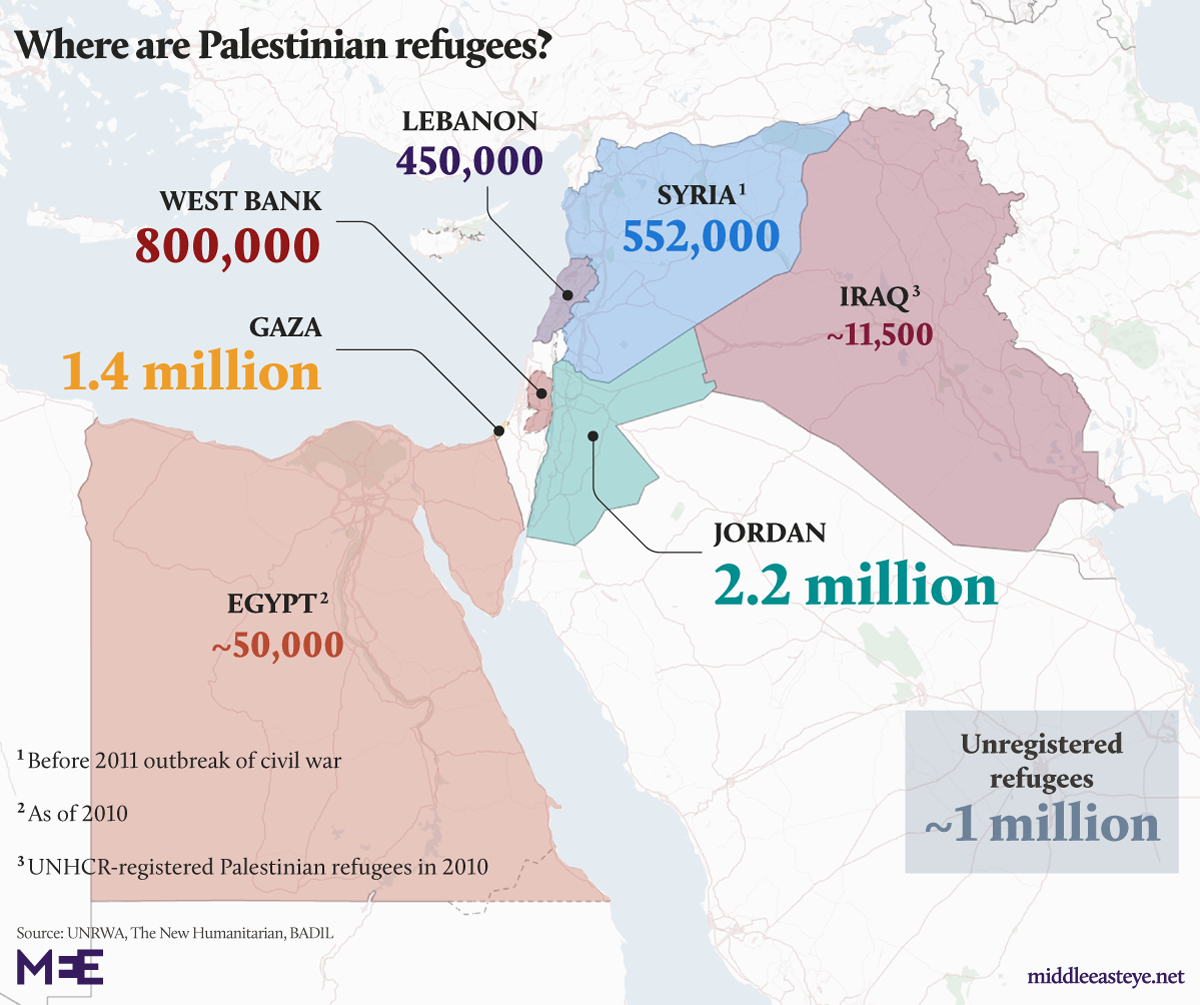

An estimated 750,000 Palestinians fled or were forcibly driven from their homes by Jewish paramilitary groups as the Israeli state came into existence in 1948.

That number amounted to more than half of the Palestinian population at the time, according to United Nations data. Seven decades after that modern-day exodus, almost 5.5 million of these Palestinians and their descendants are registered with the United Nations as refugees.

About 2.2 million refugees live in dozens of refugee camps across the occupied West Bank and Gaza, with the majority of others living in the neighbouring countries of Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

The “right of return” for Palestinians displaced by the conflict was established in Resolution 194 passed by the United Nations General Assembly in 1949, and reiterated by the same body in another resolution in 1974, which called its implementation “indispensable for the solution of the question of Palestine”.

It is supported by other international resolutions and conventions affirming more generally people’s right of return to their homeland.

The fight over the right of return

But the right of return has long been viewed by Israel as representing a demographic threat to its self-identification as a Jewish state. The population of Israel in 2017 was 8.7 million, according to World Bank data, of which about 20 percent are Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Accordingly, Israel’s position in negotiations has been shaped by an unwillingness to countenance the potential prospect of millions of Palestinians returning to their homes.

The Oslo Accords of 1993 established the Palestinian Authority (PA) as an interim governing body with the stated aim of creating an independent Palestinian state by the end of the century.

The deal called for the establishment of a permanent settlement to conflict within five years, by which point an agreement on “final status” issues - such as Israeli settlements, the fate of Jerusalem and refugees - would be presumably reached during a second stage of negotiations.

But when the five-year deadline arrived in 1999, all attempts to reach a permanent settlement had failed.

Between 2000 and 2001, when then-US President Bill Clinton sought to reach a new agreement during summits in Camp David and Taba, the Israeli position fluctuated.

At Camp David, the famous presidential retreat in Maryland, then-Israeli chief of staff Gilead Sher wrote that Israeli negotiators understood any agreement allowing refugees to return would involve no less than 100,000 people.

The establishment of an international fund worth between $10 to $20 billion to help permanently resettle remaining refugees in their host countries was also discussed - a scenario favoured by Israel.

But by the time the parties reconvened in the Egyptian resort of Taba six months later, the Israelis aimed for it to be abandoned altogether.

In a cabinet meeting ahead of the Taba summit, the Israeli government stated that one of its most basic positions in the talks was that “Israel will never allow the right of Palestinian refugees to return to inside the State of Israel”.

The negotiators discussed compensating Palestinian refugees, but again could not reach an agreement. Palestinian negotiators discussed restitution and compensation based on property valuations, while the Israelis discussed compensation in terms of a fixed sum alone.

The timing of the Camp David and Taba summits so close to both US and Israeli elections doomed the talks to never reach a successful conclusion.

By 2004, Tzipi Livni, Israel’s minister of Immigrant Absorption at the time and centrist politician, had reportedly convinced US President George W. Bush to adopt Israel’s wholesale rejection of the right of return as his own - an uncompromising position US Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice later said struck her as “a harsh defence of the ethnic purity of the Israeli state”.

Israelis and Palestinians continued to disagree over the refugees issue in the next major peace talks initiated by US Secretary of State John Kerry from 2013 to 2014.

Netanyahu rejected the Palestinian right of return and made recognition of Israel as a Jewish state a requirement for peace but PA President Mahmoud Abbas refused, arguing it would compromise the claims of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes.

UNRWA in the crosshairs

Now, US President Donald Trump’s so-called “deal of the century”, coupled with his decision to end US funding for UNRWA, the UN Relief and Works Agency that supports the millions of Palestinian refugees, appears to be an attempt to remove the issue from the table completely.

Created by the United Nations as a temporary organisation in December 1949, UNRWA has provided education, healthcare, infrastructure and emergency relief services for displaced Palestinians ever since, as well as employing thousands in the occupied territories.

Operating in Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza, UNRWA continues to see its mandate renewed every three years and is funded almost entirely by voluntary contributions from UN member states, among whom the US has been the biggest donor for decades.

Last August, it was reported that Trump intended to change US policy towards Palestinian refugees so that descendents of those displaced in 1948 and the 1967 Arab-Israeli war would not be counted.

This would reduce the number to about 500,000, or about a tenth of the number currently recognised and supported by UNRWA.

It also brought Washington in step with Israel, which argues that the inherited refugee status passed on from the initial generation of displaced Palestinians to their descendants is unique to Palestinians and inherently "perpetuate[s] the conflict".

Welcoming an end to US funding for UNRWA, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said the US had “done something very important by stopping the funding for the refugee-perpetuation agency known as UNRWA”.

“It is finally starting to solve the problem. The funds must be taken and used to genuinely help rehabilitate the refugees, whose true number is a fraction of the number reported by UNRWA,” he said. “This is a very welcome and important change, and we support it.”

Netanyahu has also pointed out differences between the definitions of a refugee used by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and UNRWA, and called for the UNHCR to gradually take over UNRWA’s mandate.

The UNHCR definition discludes anyone who has subsequently acquired citizenship of another country from holding refugee status, but UNRWA counts as refugees those with other citizenships and those who are descendants of the first generation displaced from their land.

UNRWA has repeatedly debunked accusations of special treatment for Palestinian refugees, and placed responsibility for the continued refugee crisis squarely on the shoulders of the inconclusive peace process.

Why is Trump going after refugees?

Meanwhile, the halting of US funding for UNRWA has thrown the futures of millions of Palestinians across the region into further uncertainty and upheaval.

Trump has argued that the US has made large financial contributions to Palestinians without getting sufficient "appreciation or respect" - and implied cuts to aid were a means of pressuring Palestinian leadership into negotiations over the “deal of the century” peace plan.

Despite international resolutions and conventions addressing the issue of refugees, past peace talks have largely failed to address in any concrete way the fate of the Palestinians in exile.

Some therefore see Trump’s dismantling of UNRWA and his push to remove the majority of Palestinians from the record as refugees as part of a plan to push through a deal in which one of the main points of contention in previous rounds of talks has simply been removed from the discussion.

However, some observers have pointed out that the US’s long history of financing Palestinians falls squarely in line with its support of Israel.

The outsourcing of humanitarian aid to international organisations and world powers, they argue, has let Israel off the hook for its own responsibility as an occupying power to provide for civilian populations under its control, as defined under international law.

Those concerns appear to be shared by some Israeli officials. In September, it was reported that Israeli security officials had urged their government to find an alternative source of aid for Gaza because of fears that an end to UNRWA funding could lead to a further deterioration in the enclave's humanitarian situation and an eventual war.

The steep decline in aid, therefore, could backfire - as Palestinian refugees, the majority of whom still hold on steadfastly to the hope of returning to their homeland, may now find themselves with even less to lose.

No comments:

Post a Comment