Declassified documents reveal how UK propaganda unit used Friday sermons, newspapers and novels to spread anti-Communist messages across Middle East

By Ian Cobain

British government propaganda unit ran covert campaigns across the Middle East for several years at the height of the Cold War, distributing Islamic messages in a bid to counter the appeal of communism.

Recently declassified official papers show that the Information Research Department (IRD), a then-secret division of the UK Foreign Office, commissioned a series of sermons that were reproduced and distributed throughout the Arabic-speaking world.

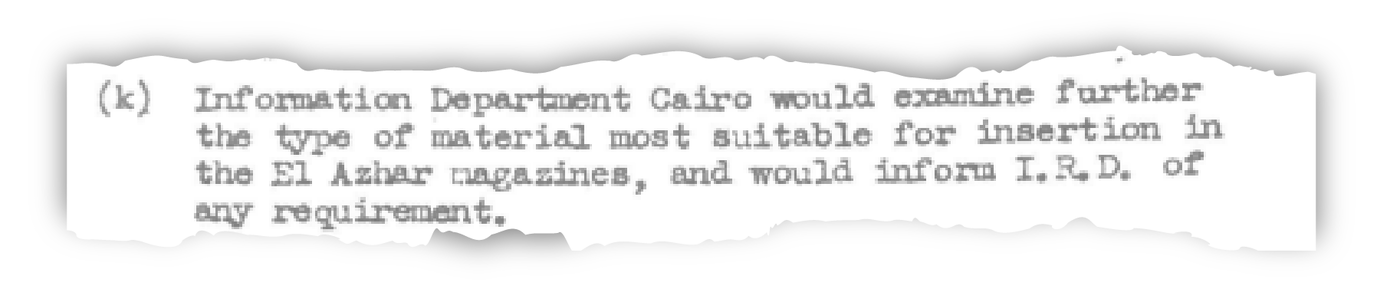

The papers show that the unit also arranged for articles to be inserted in magazines published by Al-Azhar University in Cairo, “to ensure that every student leaves the University a resolute opponent of Communism”.

In an attempt to reach as wide an audience as possible, the IRD also published and distributed across the region a series of Arabic-language romantic and detective novels, within which anti-communist messages were embedded.

These stressed that Soviet communism was essentially atheistic in philosophy and practice, and claimed that Moscow aimed to sow political disorder and economic chaos in the Middle East.

The papers also shed new light on the way in which the British government covertly controlled or influenced many of the radio stations and news agencies in the Middle East from the 1940s to the late 1960s. Some details of these operations became public after the IRD was shut down in 1977.

However, the latest tranche of declassified papers appear to show the IRD to have been particularly sensitive about what its officials termed “religious operations”, in which they attempted to utilise Islam as a bulwark against communism.

Marked Secret or Top Secret, many of the papers are being declassified after 50 or 60 years; nevertheless, some passages were blacked out by government censors before they were made public at the UK National Archives.

Subterfuge, bribery and sermons

The IRD was set up in 1948 in order to continue the work of a wartime body called the Political Warfare Executive. For the next 29 years it ran a number of newspapers, magazines, news agencies, radio stations and publishing houses, in order to spread unattributed anti-communist propaganda across much of the world.

Its favoured method, however, was to place stories in established newspapers and to covertly brief opinion formers. This was achieved on occasion by subterfuge or bribery, although early on, a senior IRD official, John Peck, warned that bribery might not always work.

“I have serious doubts about the value of bribery as a means of getting anti-communist articles in the press,” he wrote.“I am told that except in Jordan and possibly in Syria the circulation of those Middle East newspapers which are open to bribery is small and their individual influence negligible.”

In the same memorandum, he summed up the reason for IRD material being distributed without attribution:

“However valid our arguments may be, the fact that they are our arguments makes them suspect to the Arabs. We can only overcome this difficulty by presenting the same arguments through an Arab intermediary.”

Despite Peck’s wariness, bribery continued to be used as a means of distributing propaganda material across the region.

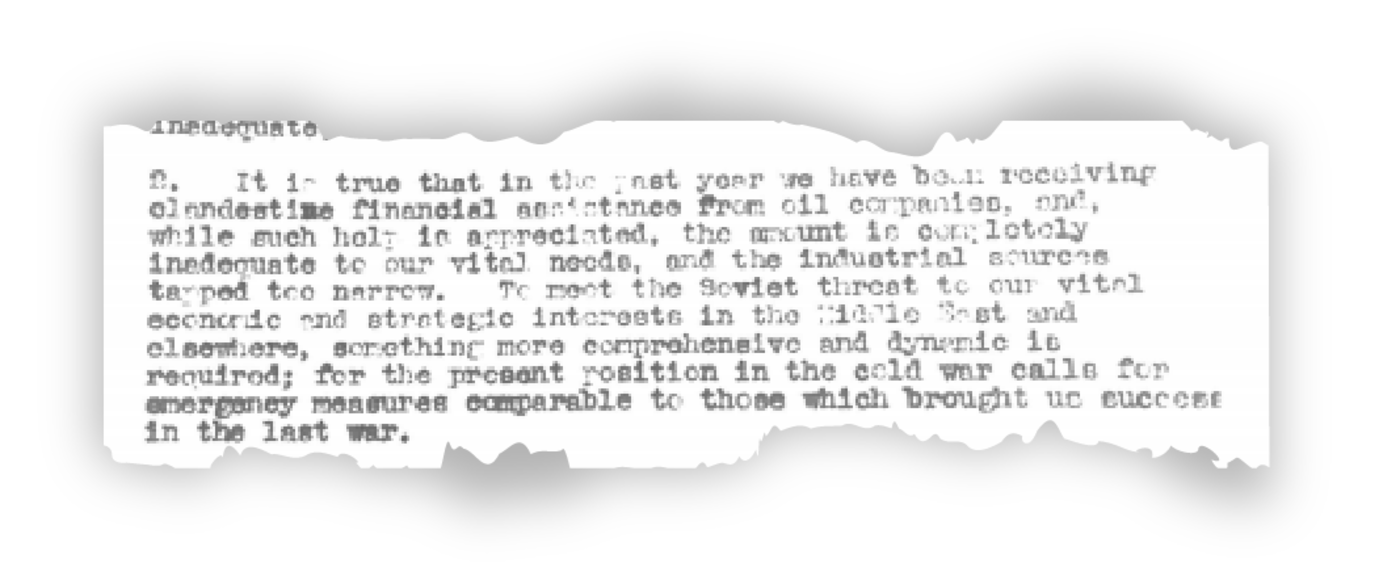

Although financed through the same unpublished budget as Britain’s intelligence services, the newly-released papers show that the IRD also received funding from the oil industry.

“It is true that in the last year we have been receiving clandestine financial assistance from oil companies,” a memo to IRD director Ralph Murray, marked Top Secret, noted in 1954.

But the Middle East was seeing “the emergence of a state of total ideological warfare”, the author claimed. “And while such help is appreciated, the amount is completely inadequate to our vital needs.”

The newly declassified papers contain a number of references to “religious operations”. Frequently these references are concerned with the financing of such propaganda campaigns, rather than the means of delivery. “You will note that we are including new budgetary provision for £1,000 to cover ‘Religious Operations’” is one typical entry.

Some details of the campaigns do emerge, however. In February 1950, for example, two years after the IRD was set up, its representative at the British embassy in Cairo informed London: “The Friday sermon has always been recognised as one of the most important way [sic] of spreading propaganda in the Moslem world.”

“We have now devised a scheme for ensuring that anti-Communist themes are adequately dealt with. A series of sermons has been written here.”

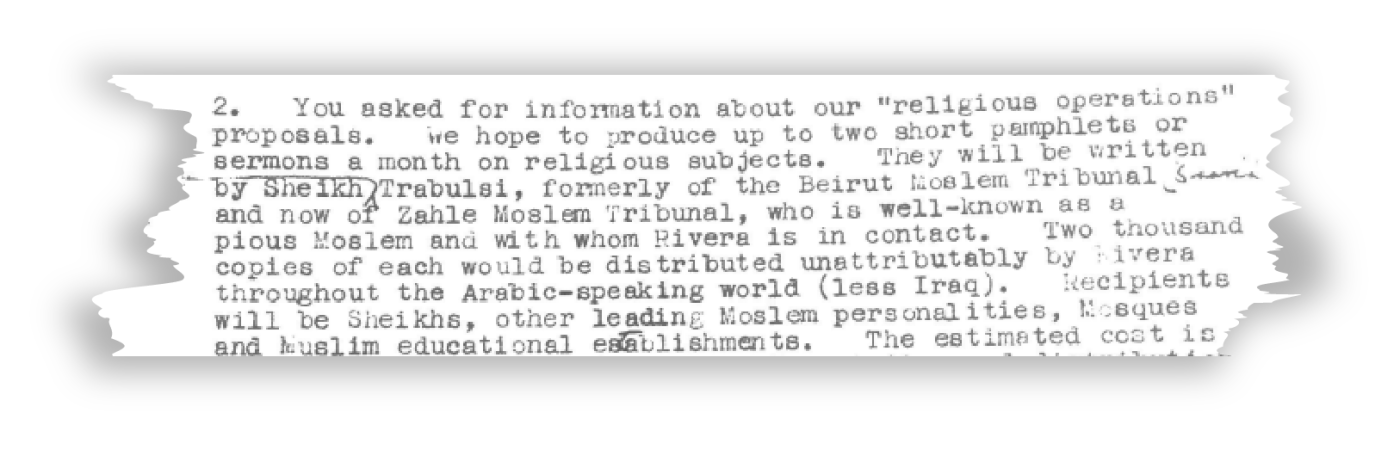

This was still happening 10 years later, as a top-secret memo from Beirut from August 1960 makes clear: “We hope to produce two short pamphlets or sermons a month on religious subjects. They will be written by Sheikh Saad al Din Trabulsi, formerly of the Beirut Moslem Tribunal (sharia) and now of Zahle Moslem Tribunal, who is well-known as a pious Moslem.”

“Two thousand copies of each would be distributed unattributably … throughout the Arabic-speaking world (less Iraq). Recipients will be Sheikhs, other leading Moslem personalities, Mosques and Muslim education establishments.”

The intermediary between the IRD and Trabulsi is named in the files as a man called Rivera, although this is possibly a codename.

Another intermediary between the IRD and individuals described as “religious operators” is named in the files as Talaat Dajani, a Palestinian refugee living in Beirut. Dajani later moved to London, where he received a medal of honour from the Queen in 1979, and died in 1992.

The whole Trabulsi operation, the IRD representative explained to London, would cost around 8,800 Lebanese pounds, or around £1,000 sterling, a year.

Although Iraq was excluded from that campaign, the country was on occasion the subject of IRD religious operations. In 1953, for example, IRD headquarters wrote to its man in Baghdad, saying: “We would like to know more about your ‘pilot’ scheme for the covert dissemination of propaganda in the Shia holy places since it may suggest ideas which could be used outside Iraq.

“Is the scheme connected with the working party’s proposal to make Friday sermons prepared in Beirut available to certain Shia divines?”

IRD officials saw another chance to make use of “religious operations” in Iraq following the attempted assassination of the country’s prime minister, Abd al-Karim Qasim, as he was being driven through Baghdad in October 1959.

There had been a “remarkable religious revival” following the attempt, the unit noted. “Workmen engaged in demolition work near the site of the attempted assassination had discovered the tomb of a Moslem holy man; this story had been widely publicized and had given substance to the popular belief that the Premier had been miraculously preserved. It was agreed that there would be an advantage in giving wider circulation to the story.

“Religious stickers have been appearing in Baghdad and the possibility of augmenting them is to be considered.”

Disruption and influence operations

The following April, a conference of Middle East-based IRD officers was held in Beirut. The minutes of what was described as a “restricted session on covert propaganda” show that Ralph Murray “listed the targets at which we should aim to disrupt or influence”.

Those to be disrupted included communist parties and hostile propaganda agencies. This was at a time when printing presses inside Soviet embassies were thought to be producing 10,000 copies of a newspaper entitled Akhbar every day.

Those to be influenced, on the other hand, included young people, women, trades unions, teachers’ organisations, the armed forces and religious leaders.

The representative from the British embassy in Baghdad explained that Iraq “was now an important target for religious material”, at which point, the minutes say, IRD officers based in Amman and Khartoum “also pressed strongly for supplies of sermons and religious articles, which they said they could easily place”.

The files make clear that several governments in the region connived with the IRD and would assist in the distribution of sermons and the placement of newspaper and magazine articles.

The IRD’s man in Baghdad also “emphasised that the Iraqi army was an important target” and suggested that arrangements might be made for selected officers to visit the UK, with the trip appearing to be arranged by bodies with no clear connection to the British government.

He also noted that in Basra, the same press was being used to print both communist and non-communist newspapers, and said that “the judicious use of some financial inducement would probably make it possible to put the Communist paper out of business if that were thought to be desirable”.

Delegates were briefed on the propaganda efforts of other members of the Baghdad Pact: the Cold War alliance of Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Pakistan and the UK that was dissolved in 1979. The IRD enjoyed extensive contacts with Baghdad Pact governments, offering both propaganda materials and technical support.

“In practice,” the delegates were told, “only the Turks are really active, having achieved the publication in the Turkish press of 25-30 articles a month prepared by a writers’ panel.”

Finally, the secret conference was informed that HMG [Her Majesty’s Government] was running two newspapers published in Bahrain: al Khalij and its English-language sister paper, the Gulf Times.

One paragraph in the minutes of the session notes that delegates were told that these newspapers were “exceptional”, in that IRD “preferred to work through staff of established newspapers”.

These minutes are among the papers that have been declassified and handed to the UK National Archives. But, 60 years after the conference, the subsequent paragraph remains blacked out.

Nasser and the Suez crisis

From the end of the Second World War to the late 1960s, successive British governments appear to have used intelligence and propaganda in an attempt to preserve strategic and economic interests in the Middle East at a time when they were struggling to retain influence.

Earlier disclosures about the IRD’s activities have shown that while some senior British diplomats in the region were highly enthusiastic, others were sceptical, fearing that exposure would exacerbate anti-British sentiment.

This is exactly what did happen, at a time and place where the British were about to take their last fling of the imperial dice: in 1956, in Egypt.

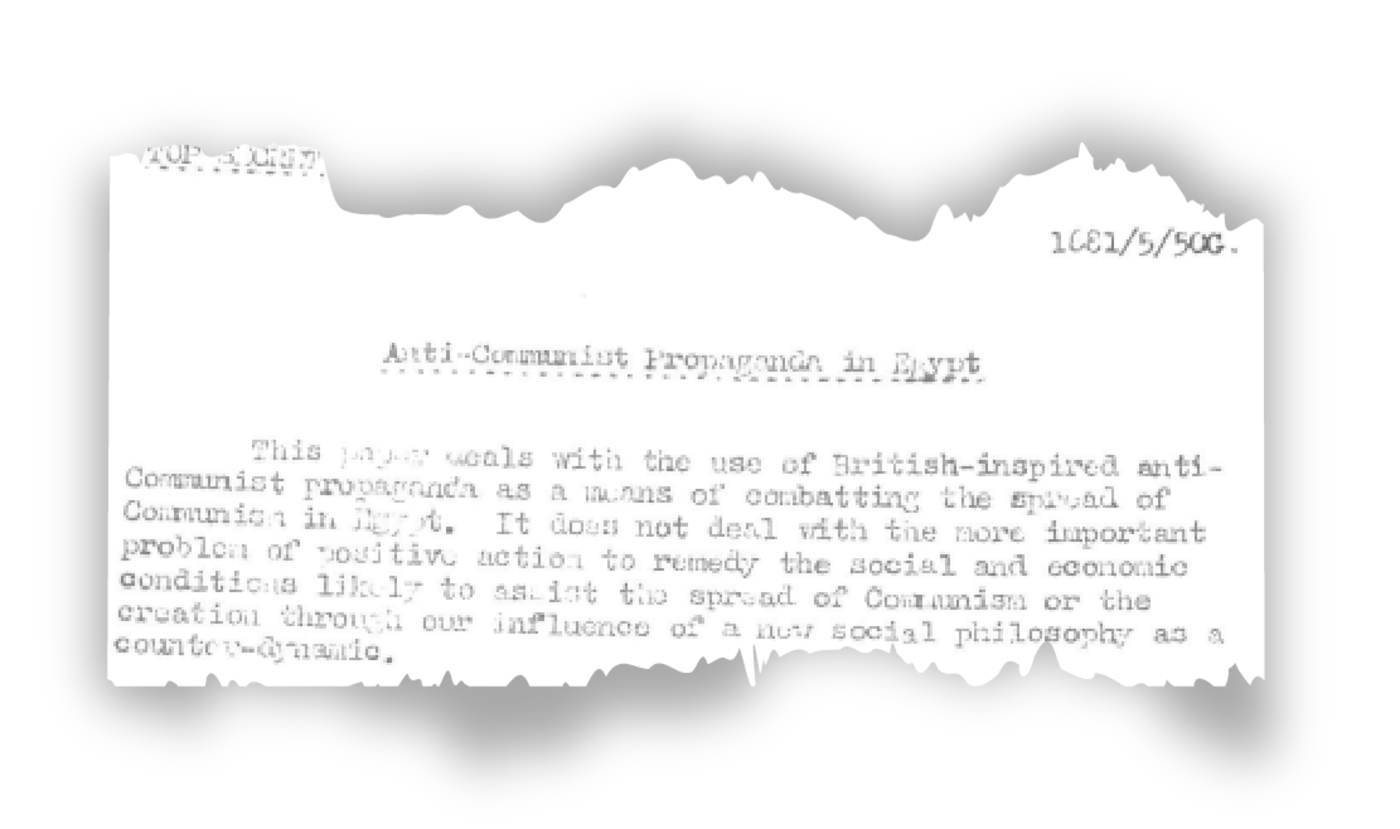

The IRD had been highly active in Egypt from the organisation’s inception. As an IRD paper written in Cairo in 1950 noted: “Conditions in Egypt are such as to make it eminently suitable breeding ground for Communism.”

The author went on to highlight “acute maldistribution between rich and poor” and the concentration of land in the hands of a small proportion of the population.

Nevertheless, he wrote:

“This paper deals with the use of British-inspired propaganda. It does not deal with the more important problem of positive action to remedy the social and economic conditions likely to assist the spread of Communism.”

Instead, the author explained, the IRD was targeting the students at Al-Azhar University on the grounds that “from among them come the Imams who preach the Friday sermon in every Egyptian Mosque; the teachers of Arabic in the secondary schools and all teachers in the village schools; and the lawyers specializing in Moslem law”.

The organisation was also arranging for “the production in drafts in English of short love or detective novels, or thrillers, embodying anti-Communist propaganda but following their local counterparts as closely as possible in presentation etc.

“The Information Department, Cairo, would arrange for the drafts to be rewritten in Arabic by local hacks, and for them to be published locally.”

The unit would also “investigate the feasibility of producing short love or thriller magazine stories (of about 2,000 words) with an anti-Communist twist”.

The jewel in the IRD’s crown in Cairo was the Arab News Agency (ANA), one of several media organisations that British intelligence had set up during the Second World War.

Like other news agencies and radio stations that had been established in Beirut, Tripoli, Sharjah, Bahrain and Aden, ANA came under the control of the IRD after that organisation was founded in 1948.

To those on the outside, ANA appeared to be part of Hulton Press, a large company owned by Edward Hulton, a Fleet Street media baron. In fact, Hulton had allowed his company to give cover to the IRD and Britain’s overseas intelligence agency, MI6.

As well as distributing genuine news stories, gathered by Egyptian and British journalists, the agency disseminated propaganda produced by IRD, and became a base for MI6 officers masquerading as journalists.

In March 1956, with relations between the UK and Egypt deteriorating sharply, the UK Foreign Office instructed the IRD to switch its focus away from communism and towards the government led by Gamal Abdel Nasser – who had been engaged in propaganda operations against the British for some years.

The following July, after Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal Company – taking control of the waterway that the British considered to be the jugular vein of their empire – the UK’s propaganda and espionage efforts under the cover of ANA rapidly picked up pace.

Anthony Eden, the British prime minister, had long been convinced that Nasser was under the influence of the Kremlin – although the British ambassador in Cairo, Humphrey Trevelyan, disagreed – and MI6 began considering whether the Egyptian president could be assassinated.

Poison gas was one favoured option; an exploding electric razor was another.

Instead, as the Suez Crisis began to unfold, Eden vetoed the murder plot and the British decided to engage in several months of psychological warfare in Cairo, followed by military intervention.

A powerful new radio transmitter was erected in Iraq, broadcasting programmes from Arabic stations around the region that were covertly under British control, an operation that was for a while given the codename Transmission X.

As the British, French and Israelis plotted to invade Egypt and occupy the area around the canal, a steady stream of IRD and MI6 propaganda specialists began to appear at the ANA’s offices in Cairo.

This had not gone unnoticed by the Egyptian government, however, and in August, just weeks before the invasions, all of the agency’s operations – news reporting, spreading propaganda and gathering intelligence – were brought to an abrupt halt.

Egyptian secret police raided its offices and the homes of several of its staff. Eleven Egyptians were accused of being spies working for MI6 officers based at the agency; one, Sayed Amin Mahmoud, a teacher, was executed, and his son, a naval officer, was jailed for life.

Two MI6 agents who helped to manage the agency were subjected to lengthy interrogation and jailed. Others were tried in their absence, and two British diplomats and four journalists were expelled.

However, the British head of the agency – who was also a correspondent for the Economist and the London-based Times newspapers, escaped arrest: it appears that the Egyptian government may have been feeding him disinformation, and wished to continue.

In the event, IRD simply set up a new Arab News Agency, from offices in Beirut, with staff in London, Cairo, Amman and Damascus.

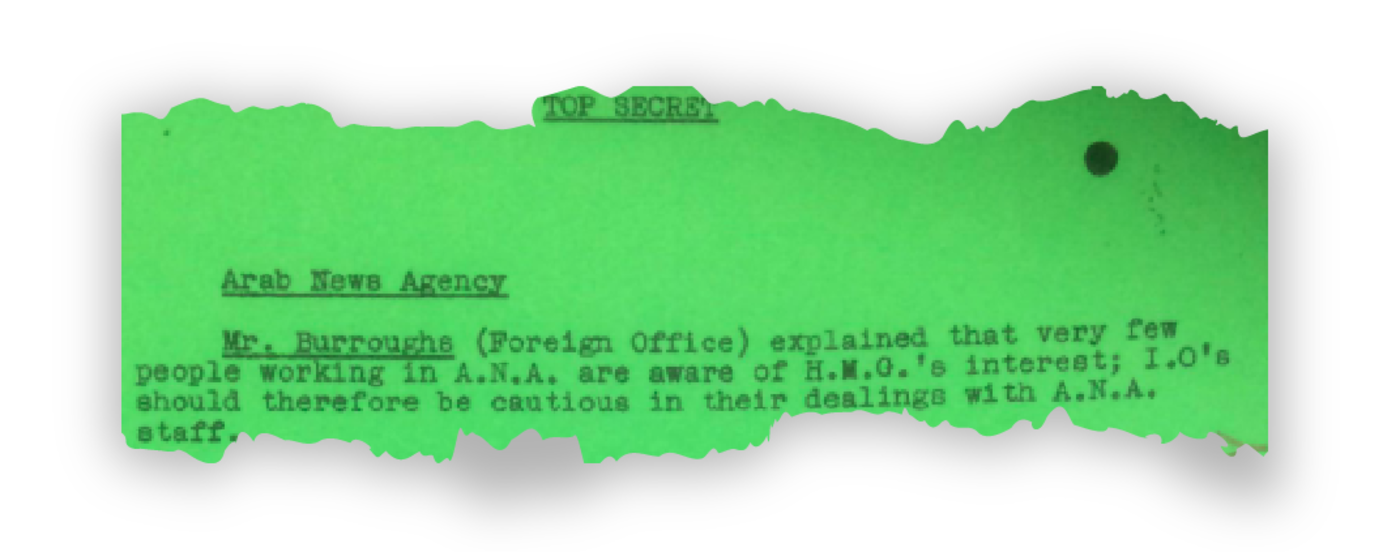

By 1960, according to one of the recently-declassified files, few people working at the agency’s Beirut headquarters were aware that it was controlled by the British government; IRD staff were warned “therefore to be cautious in their dealings” with them.

In March that year the senior IRD officer at the British embassy in Beirut wrote to London to say: “Of our secret information operations, I … attach the greatest importance to the Arab News Agency. There is no doubt they are doing the most useful work throughout the area and they run a good office here.”

Reuters and the BBC

The recently declassified documents also shed new light on the way in which in the 1960s the British government persuaded Reuters, the international news agency, to take over the operations run by two IRD fronts, Regional News Service (Middle East) and Regional News Service (Latin America). The relationship between Reuters and the IRD was first exposed in the 1980s.

The government funded these Reuters operations through the BBC. It began paying the BBC enhanced fees for its World Service operations, and the BBC in turn paid Reuters extra sums for receiving its news feed.

While the IRD accepted that it could not exercise editorial control over Reuters, the declassified papers show it did believe that it would gain “a measure of political influence”.

Some of the IRD’s Cold War activities in the Middle East and North Africa remain secret, however, with many of its old files remaining classified on national security grounds.

Not all of the papers on Reuters and the Arab News Agency have been transferred to the UK National Archive, for example. One dating from 1960, with the catalogue description “renegotiation of contract between Reuters and the Arab News Agency”, is among the IRD files that remain classified.

Another that has been withheld by the UK Foreign Office is known to contain papers from 1960 and is entitled “Information Research Department: Jordanian television”.

Other withheld files concern efforts to distribute IRD material through the Maghreb Arab Press news agency after it was set up in 1959, or have titles like “Information Research Department: Arab trade unions”.

Many of the titles of the classified IRD files are themselves classified: the UK National Archives catalogue simply lists them as “Title withheld”.

Reputational damage?

The United States was also an enthusiastic purveyor of propaganda in the Middle East throughout the Cold War. Material created and distributed by the US Information Service tended to promote the idea of common western and Islamic values rather than attack Communism.

The recently declassified files are all concerned with British campaigns, however.

With the IRD being shut down in 1977 – in part, because too many people had become aware of its existence and activities – two questions remain.

The first is: did their campaigns have an impact on people’s attitudes and behaviour?

Throughout the Cold War, many British diplomats in the Middle East were sceptical about the IRD’s efforts. Some argued repeatedly that communism had only limited appeal in the region, and that Arab nationalism posed a greater threat to the UK’s interests than Moscow.

Even in Iraq – which the IRD appears to have believed to be more susceptible to communist influence than Egypt – some of Britain’s envoys had their doubts.

One diplomat wrote from Baghdad to the IRD in 1955 to explain: “The Arabs have no means of checking the accuracy of our allegations about the iniquities of the Communist system … but they have the means, as they believe, of checking Russian propaganda about French and British wickedness in the Persian Gulf and North Africa.

“In our experience, it is barely possible to interest the politically conscious Iraqi in the Communist system at all.”

Looking back, a number of historians remain equally sceptical.

Vyvyan Kinross, author of Information Warriors, a forthcoming book about the battles for hearts and minds in the Middle East, believes that Eden’s attempts to demonise Nasser in 1956 left him looking hopelessly out of touch, and propelled Britain into disastrous military action.

The failed propaganda war contributed to “a general collapse of Britain’s reputation for honesty and fair dealing in the region”, Kinross says.

James Vaughan, lecturer in international history at Aberystwyth University in Wales, who has extensively studied western Cold War propaganda in the Middle East, concludes: “The history of British propaganda in Egypt demonstrates how the decline of British influence was a well-advanced phenomenon, several years before Nasser’s decision to nationalise the Suez Canal Company.”

The second question is: what happened after the IRD was closed in 1977?

An intriguing answer to this question was provided by Adnan Abu-Odeh, who served as information minister in the government of King Hussein of Jordan.

Abu-Odeh would have been on MI6’s radar at the time. He was Palestinian who had risen through the ranks of the Jordanian secret police and been handpicked for the job by the king.

At the time the kingdom was going through a major crisis, which became known as Black September, when the Jordanian Armed Forces attacked and expelled the PLO under the leadership of Yasser Arafat from the refugee camps in Jordan.

The crisis was resolved when Palestinian fighters known as the fedayeen were escorted to Syria.

In an interview with Middle East Eye in 2018, Abu-Odeh explained how he was sent to England in the early 1970s, to be trained by the IRD.

While working as an intelligence officer, Abu-Odeh said, he was approached by the country’s newly-appointed director of intelligence. “He said to me: ‘His Majesty wants you to go on a course in London at the IRD.’

“I said to him: ‘What is the IRD? I didn’t know.”

Later, he was sent back to England to study psychological warfare at a military academy.

“The king was preparing me to become minister of information, on the advice of MI6. The IRD taught me their tactics and methods.

“When I became minister of information, I trained one or two people how to do it.”

Although there is no confirmation in the recently declassified IRD files, it seems entirely possible that before it was disbanded, the organisation trained other government officials across the region.

No comments:

Post a Comment